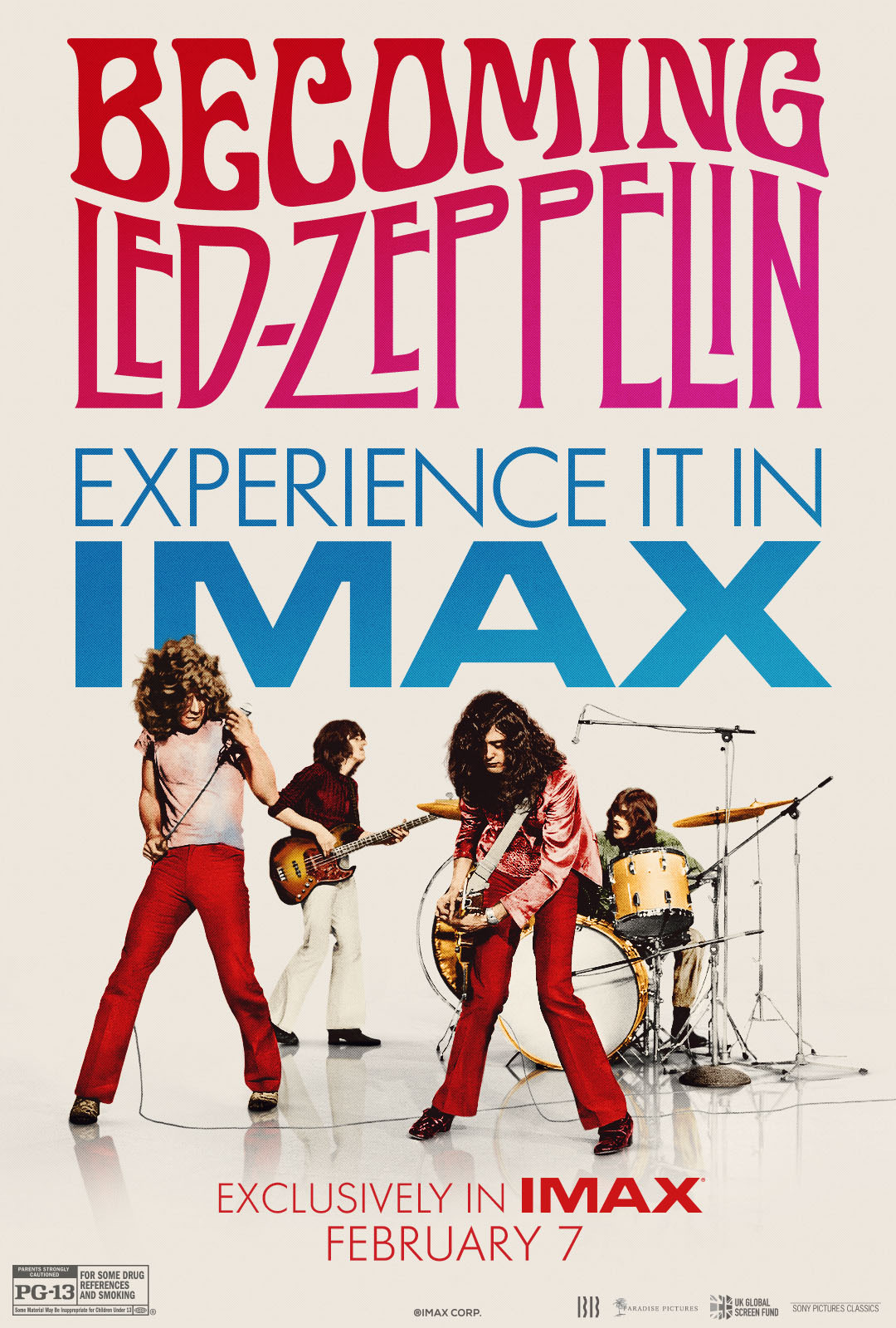

Becoming Led Zeppelin

Bernard MacMahon's documentary of Zeppelin's early days captures the band as they figure out to harness their power.

Becoming Led Zeppelin concludes with one of my favorite moments in the Led Zeppelin catalog: Robert Plant absolutely butchering the lyrics to Eddie Cochran's "Something Else," spitting out gibberish as he gallops along to the group's fuzzed-out rockabilly beat. Plant sounds so swept away by the force of his own band that he's lost track of the song's narrative arc—a blend of absurdity and exhilaration that is unique to Led Zeppelin.

This particular version of "Something Else" happened after Zeppelin stormed through "C'mon Everybody," another Cochran classic, toward the end of their triumphant gig at Royal Albert Hall 1970. The two songs play over the closing credits of Becoming Led Zeppelin, extending the film's rousing finale: the triumph of their headlining gig at the Royal Albert Hall on January 9, 1970.

Becoming Led Zeppelin ends there, right at the twilight of the 1960s, stopping the story long before the band became Golden Gods, towering like a colossus over the 1970s. That's by design. Director Bernard MacMahon and his writing/producing partner Allison McGourty chose to focus on the music of Led Zeppelin, not the myths, which is how they secured the participation of Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, and John Paul Jones, the three surviving members of the band. All three give new interviews—their late bandmate John Bonham is heard in an unearthed interview—to help elaborate and punctuate the story.

All three members are an active part of the film, strolling through their back pages and also witnessing footage excavated by MacMahon and McGourty. Page seems especially delighted at the discoveries, still giddy by the fact that he was able to execute the grand vision he developed after the Yardbirds collapsed to rubble in the waning days of psychedelia. Page chose to leave a lucrative career as a session musician behind so he could chase the same dream that consumed Jeff Beck and Eric Clapton—friends and peers who were able to play blues-based rock'n'roll decidedly hipper than the commercial sessions the guitarist mastered while still in his teens.

Page flips through an old session datebook, laughing that he played on records by everybody except the Beatles, but Becoming Led Zeppelin doesn't linger on the records by the Who and Kinks sessions featuring his guitar. Instead, Shirley Bassey's "Goldfinger" and Donovan take centerstage, highlighting the versatility of Page and John Paul Jones, a fellow session man who also played on these dates. Jones worked as bassist for hire but producer Mickey Most also enlisted him to write arrangements for Donovan and Lulu, whose earnestly ornate "To Sir with Love" feels as if it exists on a parallel plane from Zeppelin.

Then again, Plant and Bonham—a pair of misfits from the Black Country—also seemed to come from a different world than the studio sophisticates of Page and Jones. Plant in particular lived an itinerant lifestyle, enough of a vagabond for Bonham's wife Pat Phillips to warn the drummer to stay away from the singer. The pair played together in the Band of Joy, a far-ranging psychedelic outfit that so prominently featured Plant, he was billed above the band in the print advertisements featured in Becoming Led Zeppelin. Bonham went on to play with folkie Tim Rose, leaving Plant to wander without a home until Page extended an invitation to join the band he was assembling from the ashes of the Yardbirds.

All three survivors recount this prehistory quite fondly in their newly-filmed interviews, their memories interwoven with vintage clips and photos. As affectionate as Becoming Led Zeppelin can be, it escapes hagiography and nostalgia due to MacMahon grounding the film within history, occasionally resorting to a News on the March litany of headlines but usually discovering power within minute, telling details. Witness the passage where Page revisits the boathouse that was home to the band's first rehearsals; like the audience, he wonders why the racket didn't anger the neighbors.

MacMahon's weaving of contemporary and historic footage emphasizes how Led Zeppelin did not exist in a vacuum. They were a product of their time, finding inspiration in the exuberance of skiffle king Lonnie Donegan and the earthiness of Sonny Boy Williamson, benefitting from the hot house of the London studio system as well as the underground that formed in its opposition. Page could sense the divide developing in the late '60s, keenly aware that the Yardbirds became hamstrung by pop singles. His insights on how he tailored Zeppelin LPs to fit the freedom of American FM radio are sharp but ultimately this film isn't the story of Zeppelin in the studio: it's about the potency of their musical chemistry.

All through Becoming Led Zeppelin, the band is caught playing in small rooms, creating a sound that overpowers their cramped quarters. They'd later find canvasses as large as their sound—an evolution that culminated in the wonderfully ludicrous midnight movie The Song Remains the Same—but here, Zeppelin always is playing stages where there's no distance separating band members or even audience. The physical closeness makes the music seem mighty and wily: it's too sinewy, too immediate to seem pompous even when the band drifts into the foreboding cloud of "Dazed and Confused."

Not long after the January 1970 concert at Royal Albert Hall, Zeppelin added different dimensions of light and shade to their palette, expanding their folk leanings on Led Zeppelin III. There are hints of those textures here—there's an extended segment where Page discusses the fingerpicked instrumental "Black Mountain Side"—just as there are subtle, almost imperceptible nods to Middle Earth and the mystical, elements that would become a driving force of the Zeppelin mythos. What's so appealing about Becoming Led Zeppelin is that it strips away the lore and tawdry tales, instead focusing on the period when the band was in its ascendancy, figuring out how to harness their inherent power. As depicted by MacMahon, that moment still sounds vigorous and limitless.

Convinced me. IMAX tickets in hand.