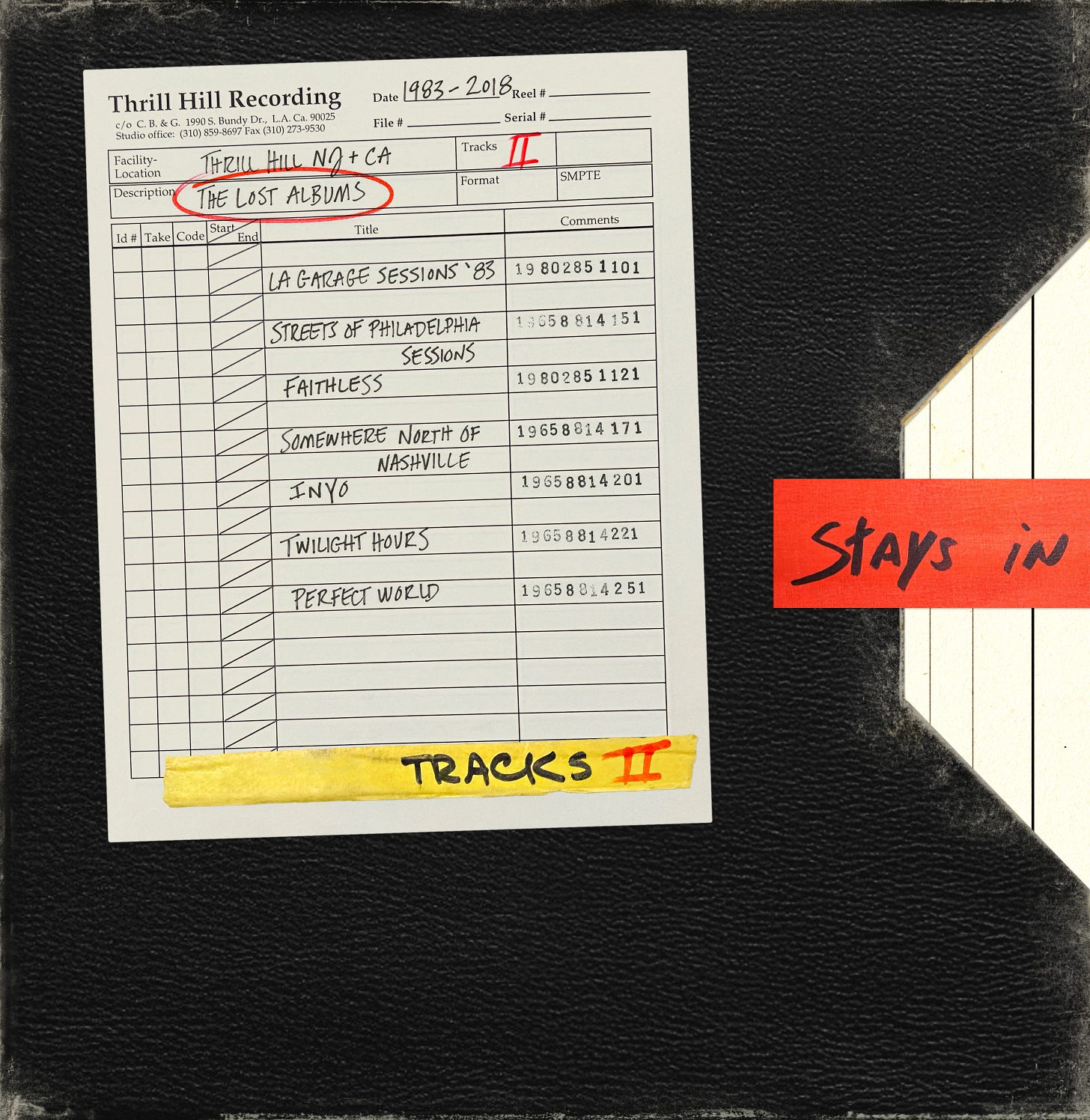

Bruce Springsteen—Tracks II: The Lost Albums

The Boss digs into his vaults and pulls out seven unreleased albums which hold their own with his official albums of the 1990s and beyond.

Bruce Springsteen—Tracks II: The Lost Albums [2025; 1983-2018]

"I often read about myself in the 1990s as having some 'lost period.' Not really. I was working the whole time."—Bruce Springsteen, in a promotional film touting the release of Tracks II: The Lost Albums

Who could blame anybody for thinking Bruce Springsteen spent the 1990s quietly? He released precisely three albums during the decade, delivering two of them on the same day in 1992. He dabbled in cinema, winning an Academy Award for "Streets of Philadelphia," the song he contributed to Jonathan Demme's AIDS drama Philadelphia. He acquiesced to a Greatest Hits a few months before the appearance of The Ghost Of Tom Joad, the last LP he released in the '90s.

That's a meager output, especially for a major artist, yet it reflects the shifts in a record business that grew increasingly dependent on blockbusters that could shift units at big box stores. Albums by superstars were expected to be events and when they didn't live up to expectations, it could deeply wound a career. This happened to Springsteen to an extent. Human Touch and Lucky Town didn't generate hits and didn't engender love, causing him to think carefully about his next move. He cut enough material during the sessions for "Streets of Philadelphia" to assemble into an album but he chose not to release it, believing he'd spent too much time in the past decade making downbeat records about complicated relationships.

Springsteen shelved another finished album before he released The Ghost Of Tom Joad, too. After spending his days sweating over the nuances of Tom Joad, he had his Nashville pros cut loose at night, storming through songs that veered closer to country than he ever had ventured before. He decided that The Ghost Of Tom Joad "was just the better record," leaving this other record in the vault where it sat unperturbed and unbootlegged until it was unveiled as one of the seven unreleased albums on Tracks II: The Lost Albums.

It's a bit difficult to grasp how greatly Tracks II: The Lost Albums expands Springsteen's discography. Over the last two decades, he's released nine studio albums, two of which are cover records, so this box set roughly matches his output of the last two decades. The purview of the set extends even further: the earliest material here dates from 1983, the latest from 2018. Save Perfect World, an enjoyable grab-bag that rounds up outtakes from the 1990s through the 2010s—it gives the album some needed vigor, distinguished by such performances as the flinty "Rain in the River"—each of these records captures a distinct moment in time.

Case in point: the opening LA Garage Sessions '83 concentrates on the recordings Springsteen made after Nebraska, as he was stumbling toward the arena rock of Born in the U.S.A. LA Garage Sessions '83 isn't as noisy as its title suggests, nor does it feel like a considered album. Songs repeat, the fidelity ping-pongs between home demos and the studio, it doesn't so much flow as plow forward. The messiness feels like a bootleg and, like a bootleg, it's exciting for its individual moments. "Don't Back Down On Our Love" is a brisk bit of rockabilly that has a cousin in "Little Girl Like You," whose sparkling pop echoes Buddy Holly. "Sugarland" is a wounded Heartland anthem, while the propulsive "Seven Tears" suggests the modern country aspirations of Tunnel of Love. In its non-ballad rendition, "Fugitive Dream" is painted with smears of synths that accentuate its haunted core.

Those synths demonstrate how a good portion of LA Garage Sessions 83 find Springsteen exploring how to use synthesizers as texture and color, a preamble to the full-fledged electronica of Streets of Philadelphia Sessions. Unlike its predecessor, Streets of Philadelphia Sessions is an album that does play like a complete thought. Redolent of signifiers of the early '90s—it hums on drum loops and stilted samples, offset by synths that crawl so slowly they seem still—Streets of Philadelphia Sessions picks up on a thread left dangling by the Tunnel of Love, extending that album's conflicted introspection so it almost feels meditative; the only time it delivers a glimmer of levity is when "One Beautiful Morning" comes galloping forth. The concentrated focus means Streets of Philadelphia Sessions holds together musically and thematically, yet it feels tethered to its time in a way many of his other albums don't.

Much of the rest of Tracks II: The Lost Albums seems suspended in time, even if all but Faithless—a soundtrack to an unmade "spiritual western" which appropriately splits the difference between country-gospel and VistaVision landscapes—have a kissing cousin somewhere in Springsteen's discography. Inyo is Californian folk that bears a resemblance to Devils & Dust, but it's sweeter and softer, finding a way to incorporate the woozy sway of mariachi bands. Twilight Hours is a companion to Western Stars that favors the romanticism of Burt Bacharach over the midnight melancholy of Glen Campbell's interpretations of Jimmy Webb. These two albums, along with the rowdy Somewhere North of Nashville, find Springsteen chasing sounds and ideas that exist somewhere to the left of the zeitgeist. He's exploring personal obsessions, deciding to leave them to himself once he's exhausted their potential. Choosing to keep these albums tucked away is akin to how he constructed Darkness On The Edge of Town, The River, or Born In The U.S.A., albums where he cut a surplus of material and assembled the parts into the picture that seemed prettiest. He kept albums in reserve because they didn't set him on the path he intended for his career.

Adding all these albums to his official discography serves a purpose, helping to build his legacy. Springsteen is reframing portions of his career that seemed tentative or unsteady, adding dimension and texture that deepens his body of work. Adding the mournful Streets of Philadelphia Sessions and the raucous Somewhere North of Nashville make Springsteen's '90s seem not as cautious. Similarly, Inyo has a warmth deliberately absent on Devils & Dust, and Twilight Hours benefits from an intimacy Western Stars avoided. These aren't necessarily revelatory—the biggest musical swing here won Springsteen an Oscar—yet the fact that the lost albums are as strong as what received an official release does come as a bit of surprise. Depending on your taste, some of these records may even sound better than the ones that did make it to market. I know I've been playing Somewhere North of Nashville often, loving the big-boned swing of "Repo Man" and the spirited rockabilly of "Delivery Man," both delivering a rock'n'roll kick that Springsteen has generally avoided in the second half of his career as a recording artist. I also have been returning to the gorgeous Twilight Hours, which seems every bit the equal of Western Stars. Maybe these first impressions will fade over time, maybe they'll strengthen, but there's one thing for certain: it's a gift to have so much good unheard Springsteen music delivered at once.

As revealed by these previously unreleased albums, it’s interesting how Bruce’s songwriting interests in country/Americana and classic pop (Burt Bacharach and his pre-rock and roll predecessors) parallel those of Elvis Costello. Yet Elvis released the albums he recorded in these genres while Bruce tucked them away until now. Perhaps, given his massive commercial success, Bruce was less open to rocking the boat and challenging his audience in this way. Whereas Elvis, with less commercial expectations on his shoulders, felt liberated to do what he wanted. That’s not a criticism of Springsteen, just an observation. I think these are the two best songwriters to emerge from the 1970s, with more in common than most people realize.