Duane Eddy: Dancing with the Guitar Man

A Farewell to the Rebel Rouser prompts an immersion into a discography filled with such LPs Duane Does Dylan, Duane A-Go-Go and The Roaring Twangies.

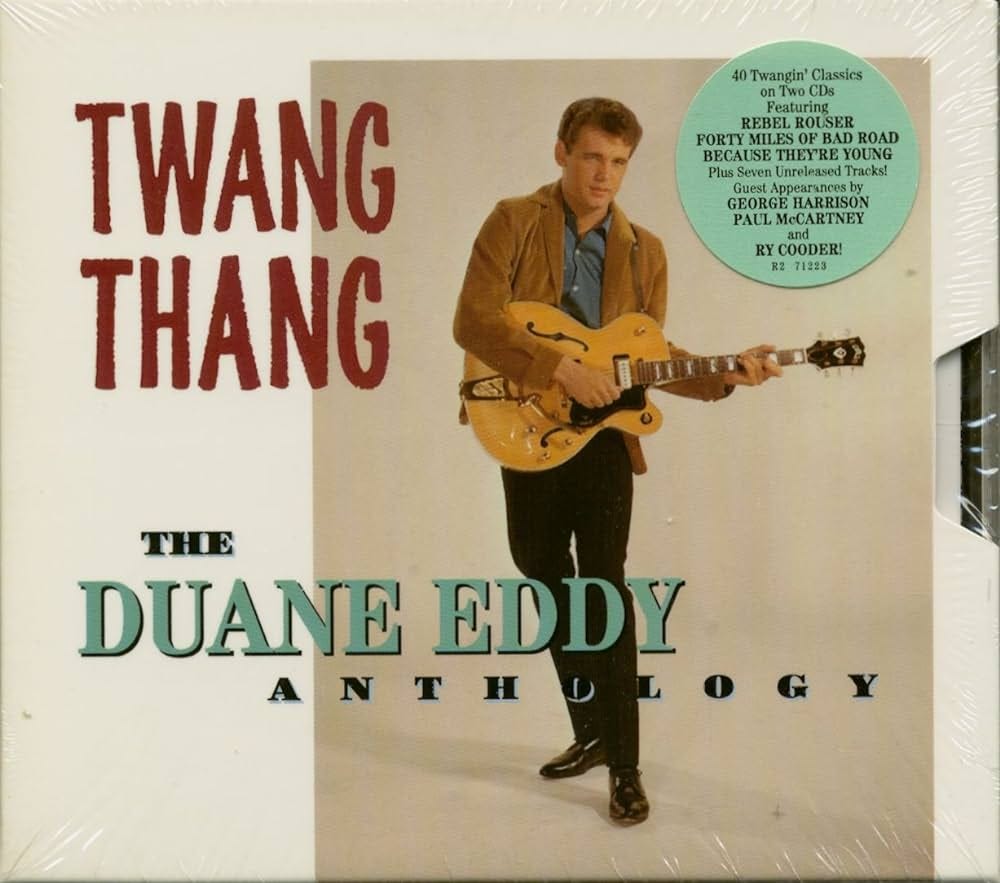

There's no disputing that Duane Eddy was one of rock & roll's first guitar heroes. In the liner notes of Twang Thang: The Duane Eddy Anthology, Rhino's definitive double-disc 1993 compilation, Dan Forte claimed "Rebel Rouser," the guitarist's breakthrough 1958 hit, "almost single-handedly established the institution of the guitar hero," placing the instrument at the forefront of rock at a time when the pounding pianos of Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis were as exciting as an overdriven six-string. Eddy never sang, a real rarity among rockers in the late 1950s, which was no handicap to his popularity during those early days of rock & roll. His twang—the name he gave the low, reverb-soaked rumble he generated with his Gretsch guitar—was every bit as distinctive and memorable as Elvis Presley's pleading or Buddy Holly's hiccups, an achievement somehow more remarkable due to the fact that he found his voice through a combination of wood, wire, and electronics.

Eddy's influence was as deep and vast as the twang of his guitar, reverberating across the decades and spanning genres. Forget the legions of surf rockers and hot rodders that popped up in the immediate aftermath of his string of Top Ten hits in the 1950s. George Harrison based his clean, economic style on Eddy and Bruce Springsteen powered "Born to Run" with a booming riff straight out of "Rebel Rouser." Long before whammy bars and stomp boxes became the tools of the trade, Eddy figured out how to manipulate his sound through Bigsby vibratos and studio effects, the first step to the pyrotechnics of Jimi Hendrix and his disciples. More than that, the records he released on Jamie—many produced by Lee Hazlewood; Eddy made his career as much as Hazlewood made the guitarist's—displayed a sonic imagination as vivid as Phil Spector but much easier to re-create on the cheap.

That's the thing about Duane Eddy's guitar heroics: unlike the double-stop blues bends of Chuck Berry, it's not hard to mimic the single-note runs of Eddy. They're licks you can learn shortly after picking up a guitar for the first time. That simplicity is uncommon among guitar heroes, particularly those who arrived during the British Invasion that swept Eddy toward the sidelines of pop, consigning the guitarist as a relic of the big boom of rock & roll.

Those early hits—"Rebel Rouser," "Ramrod," "Forty Miles of Bad Road," "Peter Gunn" and "Moovin' & Groovin'" among them—still had a presence throughout the 1960s thanks to that fathomless twang, that rumbling canyon of echo that resonates through the ages. That twang is distinctly modern, a sound that couldn't have been created without midcentury innovations that flourished within the confines of the recording studio. Eddy understood the difference. About a decade ago, he told Guitar Player magazine "It's not just playing the instrument, it's also making the record. I guess a better way of explaining it is that I don't write or arrange songs as such. Instead, I think of it was writing or arranging records. My sound is the common denominator that pulls all the threads and knits them together."

Eddy developed this aesthetic at the onset of his career with Lee Hazlewood, a DJ turned record producer who also found himself in Phoenix, Arizona. The pair co-wrote "Moovin' 'N Groovin'," lifting the intro from Chuck Berry's "Brown Eyed Handsome Man" before settling into an elastic boogie. Lacking an echo chamber, the pair jerry-rigged a water storage tank to bring out the bass in Eddy's lanky guitar. Almost immediately, they sharpened their attack with "Rebel Rouser," a swaggering number where Eddy's guitar sounds raunchy and tuneful; it was a rallying call to party.

Raunchiness didn’t become a touchstone of Eddy’s, though, certainly not in the way it defined Link Wray, the other rock instrumentalist pioneer of the 1950s. Wray's power chords strutted slowly, carrying a sense of looming danger, a menace captured on his signature hit "Rumble," which entered the Billboard charts a few months before "Rebel Rouser." Melody wasn't Wray's bag, whereas it was another a primary color for Eddy. His natural melodicism combined with his love for texture meant Eddy could play to a much broader audience than teenyboppers: if your Cinerama production needed a touch of twang, you could call in Eddy to do the job.

Eddy also had the good looks that convinced Hollywood to give him a shot in the pictures but A Thunder of Drums and The Wild Westerners didn't turn him into the next Elvis. He did wind up at RCA, the same label as Presley, churning out a series of adult-oriented LPs in the early 1960s that found him slowly drifting toward easy listening. Eddy sounded flexible and able on these records, particularly when the Twist and the Watusi were crazes—"(Dance with the) Guitar Man" gave him his last big hit in 1962— but he soon lost sight of where his audience lay. The Biggest Twang Of All, a 1966 LP that was the last time he tangled with contemporary pop, finds him playing hits by both the Mamas and Papas and Frank Sinatra, balancing James Brown's "Night" Train" with "The Ballad of the Green Berets," taking a stab at two Lovin' Spoonful covers and following up "A Groovy Kind of Love" with the title song from Broadway's Mame.

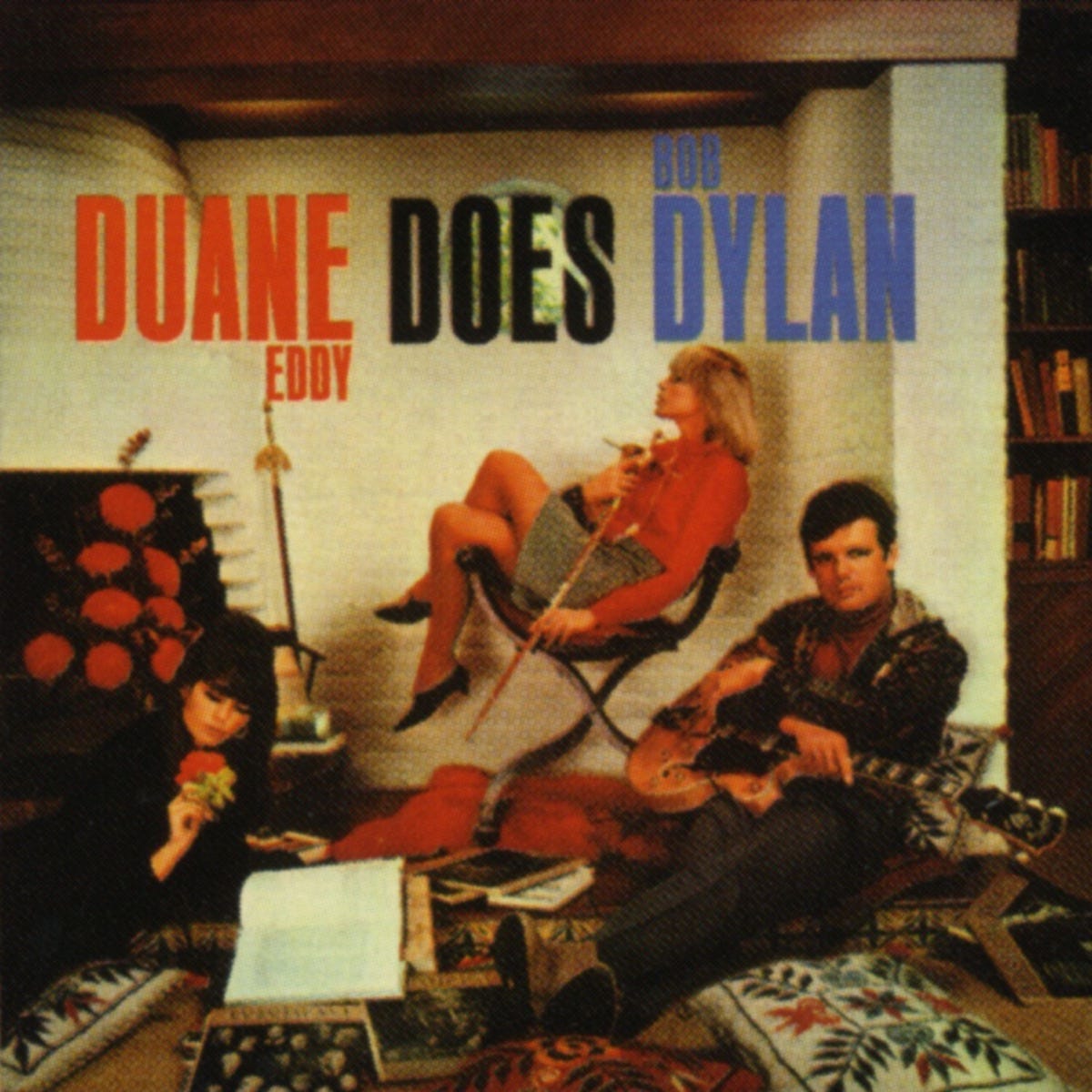

The Biggest Twang Of All is a bonafide mess yet it, like all his other mid-60s LPs, shows that Eddy is adaptable, still sounding like himself as he go-go's with Sunset strip dancers, rides the breakers on Water Skiing, mimics the Byrds on Duane Does Dylan, and indulges splashy nostalgia on The Roaring Twangies, a record as ridiculously silly as its title. These records don't precisely rock—they're quite clearly show-biz creations—yet they're livelier than the snoozy early '60s LPs. Even so, the period affections of both periods can make it difficult to hear Eddy's achievements: they're begging for some kind of cultural context.

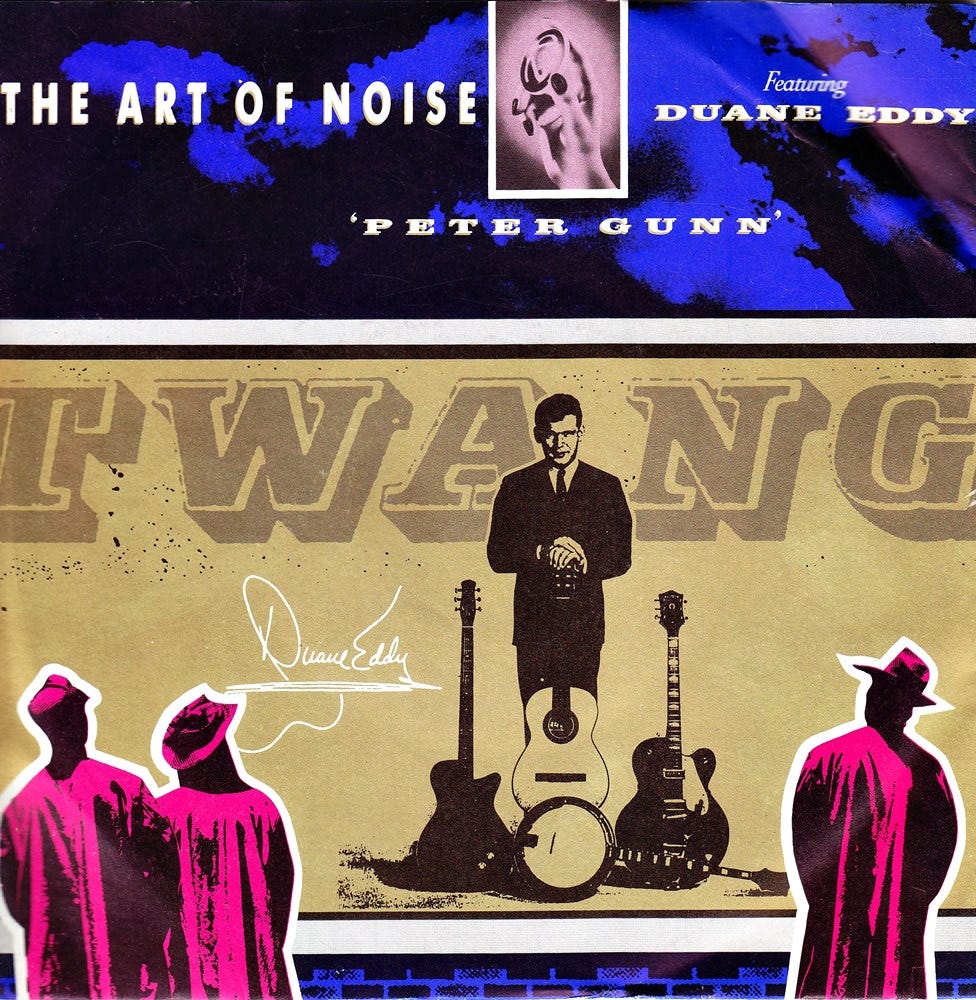

Bizarrely, the British synth-pop collective Art of Noise helped put Eddy's influence into perspective in the mid-1980s, bringing the guitarist back after an extended period in the wilderness. The guitarist spent nearly twenty years in the wilderness—he played the occasional session and dabbled in producing, never bothering with a record contract—when Art of Noise drafted him to play on their version of "Peter Gunn," the TV detective theme Henry Mancini penned in 1959 which Eddy brought to the charts in a cover not long afterward. "Peter Gunn" is a bit of a hall of mirrors in its own right. Mancini wrote the splashy tune partially inspired by rock & roll, employing piano and brass as his central instruments yet the melody slithers in such a fashion that it suggests Eddy was the composer's inspiration. Certainly, Eddy's hit rendition makes the song seem as if it belongs to him, the leaner arrangement ratcheting up the riff's inherent cool. Art of Noise cast Eddy in the central role on their cut-and-paste remake, their dance beats and electronic clamor at first seeming far afield from Eddy's Western rock & roll yet their studio craft underscores how the guitarist himself used the studio as a second instrument.

"Peter Gunn" gave Eddy an unexpected hit and Grammy—it took home the trophy for Best Rock Instrumental—helping to bring his acolytes out of the woodwork for an oversized comeback album in 1987. Bringing a pair of his original Rebels into the studio—Larry Knectel plus saxophonist Jim Horn—Eddy reunited with the Art of Noise for a pair of tracks; covered Wings's absurd "Rockestra Theme" with its author Paul McCartney on bass and production; crashed the Cloud 9 sessions so he could cut a few tunes with George Harrison and Jeff Lynne; luxuriated in Western soundscapes masterminded by Ry Cooder; and let James Burton, John Fogerty and Steve Cropper shred on a song called "Kickin' Asphalt." There is a bit of a gulf between the individual aesthetics of each group of musicians yet Eddy sounds comfortable in each setting. The guitar heroics of Burton, Fogerty, and Cropper are flashier than Eddy's laconic leads but he established the tradition of stepping to center stage with a guitar. Cooder's cinematic sweep is right in line with the old Hazlewood productions. And Eddy's economical phrasing fits into the precision-tuned productions of Lynn, making it clear the debt Harrison owes to the rocker.

Eddy didn't disappear after 1987, popping up in the oddest of places:

"The Trembler,"a song he co-wrote with Ravi Shankar for the '87 record—naturally, it featured Shankar's friend George Harrison and Jeff Lynne—showed up on the Natural Born Killers soundtrack, Eddy contributed to Hans Zimmer's score for John Woo's Broken Arrow, and the guitarist classed up "Until the End of Time," a modest adult contemporary hit for Foreigner in 1995.

A concert at the Royal Festival Hall in 2010 set the wheels in motion for Road Trip, an album co-produced by Richard Hawley and Colin Elliot that may be the first record Eddy ever made without modern sounds in mind. It's suspended out of time and its floating spaciousness emphasizes Eddy's sly versatility: "Twango" finds him nodding to the hot jazz of Django Reinhardt

and "Primeval" is the nastiest rock & roll he ever committed to tape.

Road Trip is nowhere to be found on streaming services, nor is Rhino's thirty-year-old comp Twang Thang, which is a shame as both trim away many of Eddy's excesses and focus squarely on material that wasn't thoroughly skewed by contemporary pop notions. (The same can't be said of 1987's Duane Eddy, which is also not on streaming services.) It's another reminder that while it may be easier to listen to more music than ever—in Eddy's particular case, it's possible to spin the (quite nice) Tokyo Hits LP, which only appeared in Japan in the late '60s—but it can be harder to properly hear the recordings. It's a problem exacerbated by a surplus of reissues and compilations, all seemingly covering the same territory but either delivering too much or too little of one period or keeping his early Jamie hits far away from his RCA sides. Some clever playlisting could perhaps solve some of these problems—I did not have time to assemble one myself—but it currently takes some effort to hear the best of Duane Eddy in the modern digital landscape.

My suggestions for further explorations:

Definitive

Twang Thang: The Anthology [1993; 1958-1987]

Recommended

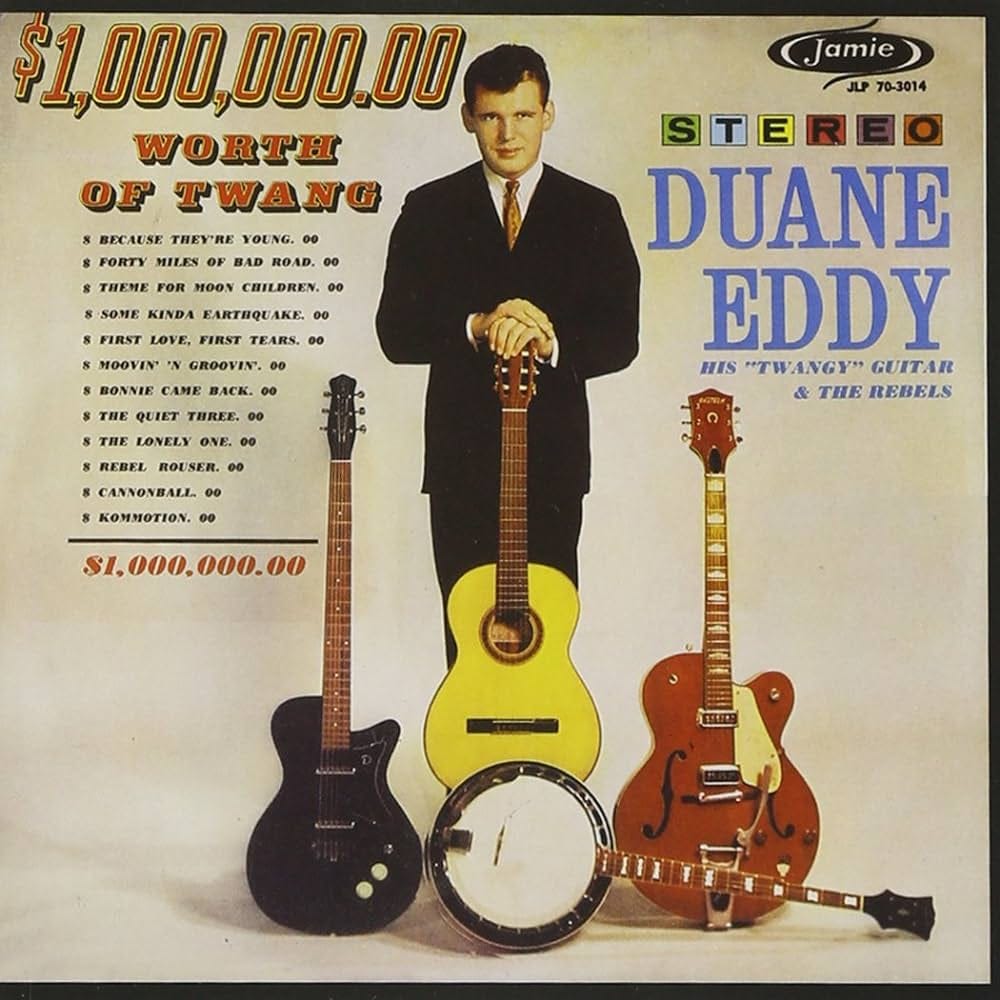

$1,000,000 Worth of Twang [1960; 1958-1960]

The best "Best Of" currently on streaming services, concentrates on the 1950s.

Road Trip [2011]

Duane Does Dylan [1965]

Duane A-Go-Go [1965]

Duane Eddy [1987]

The Best of Duane Eddy [1965; 1958-1960]

Apart from "Rebel Rouser," this focuses on the 1960s hits.

Worth A Listen

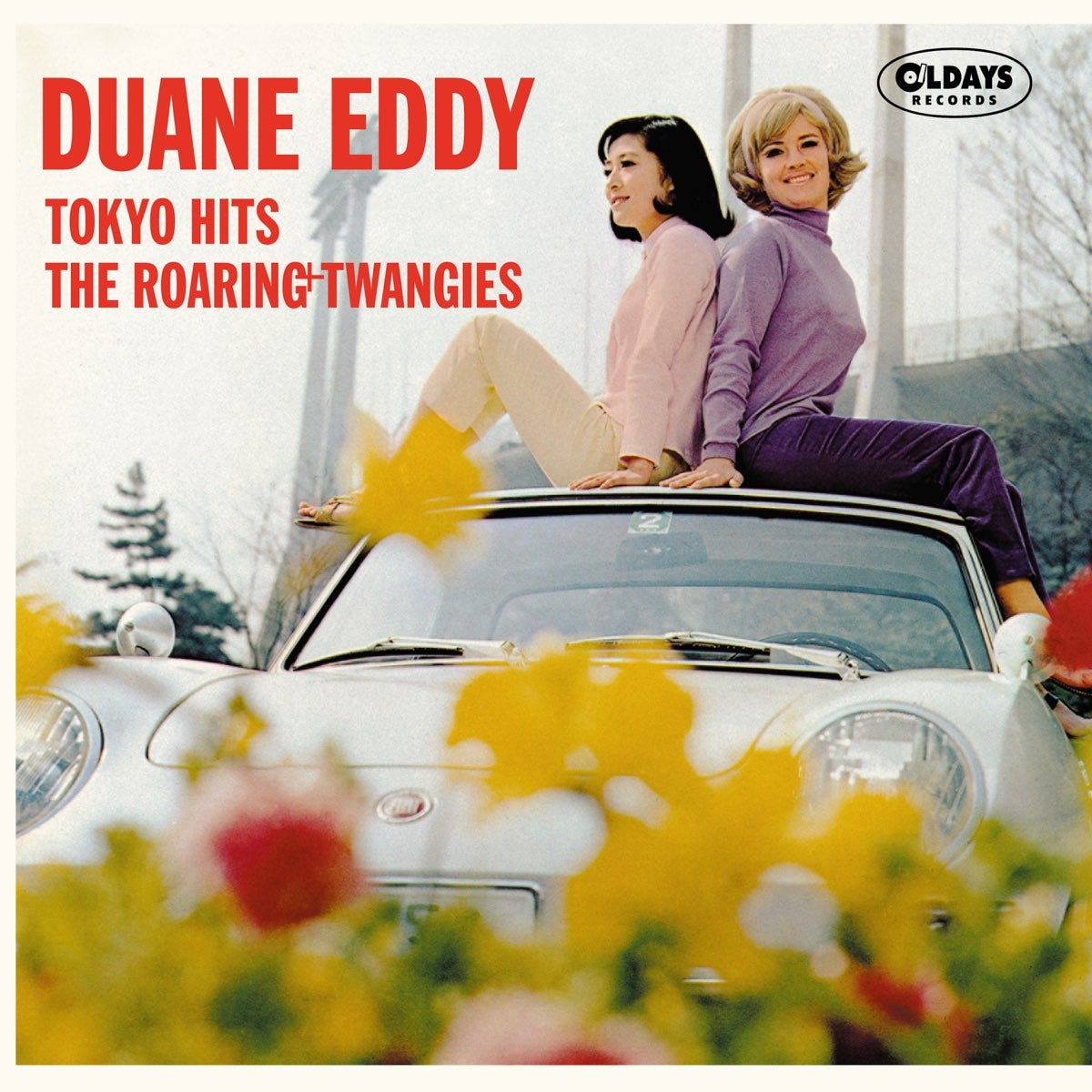

The Roaring Twangies [1967]

Tokyo Hits [1967]

Water Skiing [1965]

Dance with the Guitar Man [1963]