Eddie Van Halen: Happy Trails

Genius rarely follows a straight line. It certainly didn't in the case of Eddie Van Halen, the greatest guitarist of his generation and one of the handful of instrumentalists who shaped the sound of popular music in the 20th Century. Often, Van Halen's career seemed to resemble a supernova: a bright, blinding blast slowly decaying into aftershocks. Blame this on how his recording career with his namesake band was bookended by a flurry of activity and yawning years of quiet, a semi-retirement born of perfectionism, disinterest, and addiction. Those latter years stretched out for nearly the length of Van Halen's prime, amounting to two drifting decades filled with hiatuses, reunion tours, one strong album, and silence.

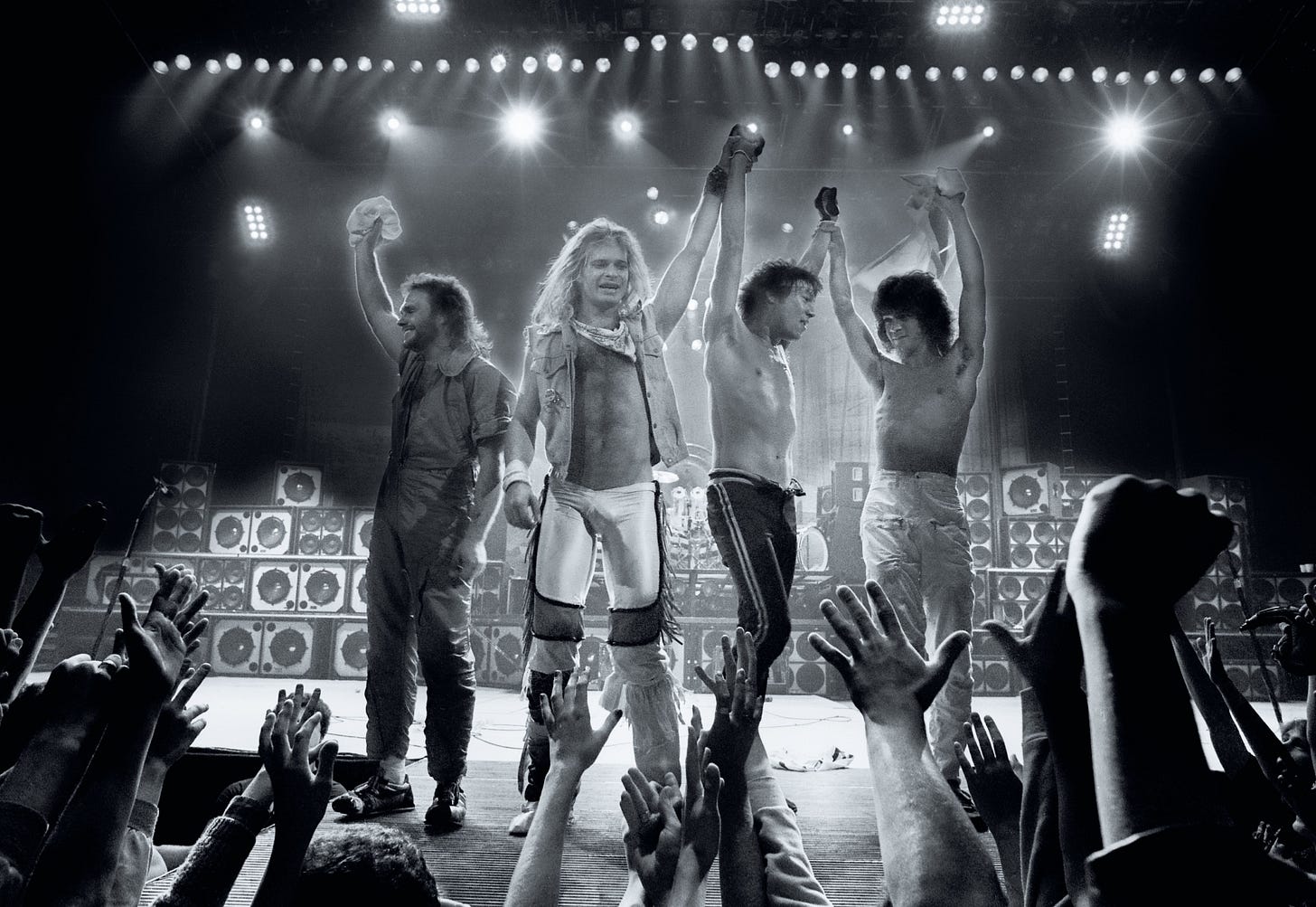

Silence never played a major role in Eddie's music. Particularly in their earliest years, Van Halen was a band who thrived at living out loud, a description that could be applied to their character as much as the volume of their amplifiers. The story of Van Halen is filled with underdogs and debauchery, fueled by a pair of outsized characters who never quite decided whether they were rivals or partners. The relationship between Eddie Van Halen and David Lee Roth was the thing of potboilers and comic books, a pair of opposites blessed and cursed to find the one person on earth who was their ideal complement.

As personalities, Eddie Van Halen and David Lee Roth seemed to provide a needed counterweight to their partner's weaknesses but even among their biggest fans, this relationship was sometimes depicted as fundamentally imbalanced in terms of talent. Eddie Van Halen possessed a rare blend of innate musicality and technical vision, a combination that could sometimes dazzle even skeptics with a disdain for metal. Roth's limitations as a vocalist were as obvious as Van Halen's gifts, leaving the lingering perception that the singer was being carried by the guitarist—a basic misreading of how bands work in general, but one that's egregiously wrong in the case of Van Halen, who was about as complicated as a band could possibly be.

Those complications were baked into the band from their beginning when Roth pushed Eddie and his drummer brother Alex to play Top 40 covers, all in the hopes they'd bring in an audience beyond misfit teenage boys. Eddie Van Halen seemed to internalize this struggle, battling impulses to please either his muse or his audience throughout his life. Parting ways with Diamond Dave didn't ease this tension. Sammy Hagar, a singer with greater technical skill than his predecessor if considerably less style, gave Van Halen the ability to roam into new territories, a freedom that grew stultifying as the group entered their ascent into middle age.

Like most rockers, middle age seemed nothing more than a distant fantasy to the young Eddie Van Halen, the one bearing a wide grin and brandishing a jerry-rigged Stratocaster bedecked in stripes. During those early days, Van Halen existed in an eternal now, a portable party that rolled through the San Fernando Valley on its way to the Sunset Strip and, eventually, the rest of the world. It wasn't that the band ignored the past—oldies were a staple of their setlists, eventually worming their way onto finished studio records—but a cover of "You Really Got Me" served as a signpost to signal how different Van Halen were from the Kinks: they were all pure id, louder and gaudier than their forefathers. So much of this was fueled by Eddie's divebombs, fingertaps, hammer-ons, and swift picking, techniques he popularized if he didn't quite invent them himself. Context was key. Other guitarists flaunted their virtuosity within the confines of prog, blues-rock, or metal, music made for self-serious listeners who appreciated sheer technical skill.

As a band, Van Halen smashed this ceiling, but before stardom, the Van Halen brothers were part of that solipsistic audience, too, cherishing chops over compositions. Eddie learned to play guitar by slowing down Cream records to a crawl so he could figure out Eric Clapton's licks, moving to Alvin Lee of Ten Years After in due time. At the dawn of the early 1970s, Alvin Lee was the definition of a guitarist's guitarist, meaning he only appealed to other six-string slingers and gearheads. Van Halen never was that kind of guitarist. Anybody who heard him play comprehended immediately his prodigious talent and skill, but it also helped that Van Halen didn't play ponderous heavy jams. Thanks to the insistence of David Lee Roth, they played hooks and melodies, the components of pop music, keenly aware that's where the crowds and girls were. Often, they got close enough to count as pop. They danced on the margins of the Top 40, deservedly getting within spitting distance of the Top 10 with 1979's incandescent "Dance The Night Away," and charming their way through a cover of Roy Orbison's "(Oh) Pretty Woman" in 1982. Plenty of other bands chased this crossover in the 1980s, so it's possible to call these hits pop-metal yet the label doesn't quite fit Van Halen; they brought pop tricks to metal, not the reverse.

Listening to the six albums Van Halen made with David Lee Roth—a process that takes a little over three hours to do—it's striking how fast and hard the records are as a combined set. The band rarely played slow songs and they never played sad ones; they had a good time, all the time. As brief as the albums are, they're hardly tight. They're filled with covers pulled from their setlists as a Pasadena party band, they frequently descend into moments where Eddie blows through the perceived limits of what sounds a guitar could produce. "Eruption," a 100-second showcase of all his techniques, represented the pinnacle of these but instrumental interludes are scattered throughout the catalog, sitting alongside such Diamond Dave-driven japes as a singalong on "Happy Trails." All these moments are in the strictest sense filler, a band figuring out how to fill a half hour in an expedient fashion, but decades later, these are the moments where the band's wild, wooly personality shines through; they're as much a part of the band as the clean, efficient "Runnin' With The Devil."

Such detours were possible during the heyday of album-oriented rock radio, when bands sustained themselves with annual albums, ceaseless tours, and radio appearances, receiving as much ink in metal rags and teen mags as they did in Rolling Stone and Creem. MTV's ascendence changed the game, a cultural shift that coincided with David Lee Roth's split from Van Halen in 1985. Things between Roth and the Van Halen brothers had been strained long before his departure. It's always been difficult to not view this tension as the result of the group reaching the end of the line with the cartoonishness of Diamond Dave's persona. The timing is telling, too. Eddie Van Halen entered his thirties in 1985 and he started acting as if it was time to leave childish things behind. Guitar magazines started calling him Edward Van Halen, a practice that would continue sporadically throughout his life, and his reputation as the greatest rock guitarist since Hendrix spurred him to try new things, ones that weren't strictly tied to guitar. Faced with the ideal opportunity for reinvention, Van Halen auditioned a bunch of singers, extended invitations to Patty Smyth and Steve Perry, who both turned them down. The group wound up with Sammy Hagar, the very definition of a meat and potatoes hard rock singer who nevertheless had chops as both a singer and guitarist, giving Van Halen a sparring partner.

Van Hagar, as this incarnation of the band has often been called, built upon the massive success of 1984 by streamlining the group's sound, swapping eccentricities for power ballads, and relying on synth-addled muscle as much as rhythmic thunder. Underneath the layers of lacquer on 5150, the band's first album with Hagar, it's possible to hear the essential elements of the band: it's easy to discern the steady thrum of Alex Van Halen and bassist Michael Anthony, while Eddie's guitar shattered the gloss. 5150 still feel the work of a different band, as this is a version of a Van Halen that sounds like they're on a mission. The sense of purpose captures the brassy attitude of the last half of the 1980s, a time when the culture aspired to be big for the sheer sake of being big. Hagar isn't so much the catalyst for this change as he is a fellow traveler, agreeing to head in the same direction as Van Halen since their destination seemed a little bit brighter. The association was mutually beneficial: Hagar knew how to modulate his arena-filling instincts enough to give the band something as bold as "Best of Bold Worlds," played along with the gilded synths of "Why Can't This Be Love" and finally gave the group a power ballad with "Love Walks In." With this hit album under their belts, the band loosened up for OU812, giving themselves the freedom to ferret jazz changes into the frenzied "Mine All Mine" and play a bit of chicken-pickin' country-rock on "Finish What Ya Started." Nothing on the album has the gonzo gusto of David Lee Roth pulling out an old hambone routine, but the band sounds spirited, nearly giddy, as they bounce from the frenzied jazz of "Mine All Mine" to the gilded ballad "When It's Love" to Sammy's ode to Cabo Wabo, a south-of-the-border fantasy that became his lifestyle.

OU812 is the sound of a band hitting cruising altitude but it wound up being Van Hagar's peak, as things went a bit pear-shaped afterward. For Unlawful Carnal Knowledge — its tortured name the result of Hagar's intense desire to have an album whose title was an acronym for "Fuck" — is wear the bloat sets in. Cut for cut, it runs clean but not lean, the songs continually pushing at the five-minute mark, resulting in an album that feels much longer than its 52 minutes. Maybe it runs long, but there's no room for eccentricities; even Eddie's interlude, "316," is a bit of mood music, not a burst of exuberance. Its efficient design meant that it was destined for the top of the charts but FUCK is oddly devoid of carnality: "Pleasure Dome" is hermetically sealed so no sensuality can creep in, it's hard to say whether "In 'n' Out" is about sex or burgers. "Right Now" gave the band an inspirational anthem but FUCK is the album is where it's possible to hear the joy seep out of Van Halen. It's a situation that plagued the band throughout the 1990s.

Hagar and Van Halen stumbled through Balance, an album where everybody involved played with the passive aggressiveness of business partners forced to set through a quarterly getaway, before the singer split in 1996. Tensions came to a head while the group attempted to complete their contributions to the soundtrack of Twister—an absurd yet fitting end to a union that illustrated how corporate rock & roll had gotten by the mid-90s. With a contractual greatest hits album looming, the band patched things up with David Lee Roth long enough for them to cut two new songs. "Me Wise Magic" conjured a bit of that old spark but the productions were so heavy, they felt dour, a situation that spilled over to 1998's Van Halen III, their maligned album with Extreme's Gary Cherone. Judged on pure chops, Cherone was the best singer Van Halen ever had but he appeared deferential to Eddie, who seemed determined neither the mistakes nor the successes he had with either Roth or Hagar. The guitar and rhythms are heavy, the songs avoid conventional hooks, requiring Cherone to work hard to sell the tracks, which he might've been able to do if they had a melody. It's a record that shows what Van Halen would be if they never joined forces with David Lee Roth: a band for gearheads.

It's impossible not to note that the thickening of Van Halen's music coincided with Eddie Van Halen's alcoholism. His addictions and vices were an open secret. Not long after Van Halen III, I had a veteran music journalist mention to me that his trick for getting a good Eddie Van Halen interview was to walk into the conference room with a six-pack of beer, thereby ensuring that the next guy would get a bunch of sloppy, unusable quotes. Eddie's health problems sidelined the band in 1999, as he took time to recover from a hip replacement surgery, but one quiet year quickly turned into a half-decade absence. The band reunited with Sammy for a tour in 2004 but Van Halen's drinking derailed some concerts and, ultimately, the group's future with Hagar. Roth re-entered the picture in 2007, the same year Eddie entered rehab, and eventually, the reunion and sobriety clicked. It's conceivable some of this stability is due to the presence of Eddie's son Wolfgang within Van Halen. Wolfgang bore the brunt of fans bemoaning the absence of Michael Anthony but A Different Kind Of Truth, the 2012 album from the latter-day Van Halen and the last record Eddie released in his lifetime, feels like a Van Halen both in form and spirit. Save Wolfgang, everybody is a little bit older and a little bit slower, but there's none of the sludginess of the 1996 Roth reunion. Eddie's playing seems relaxed in a way he hadn't since the days of OU182 and Van Halen accepts their strengths as a band, once again playing no slow songs and no sad ones.

By that point, only the dedicated cared about Van Halen finding their way back home. It had been nearly fifteen years since Van Halen III and it had been twice as long since the group was at the vanguard of metal. All of the shockwaves Eddie Van Halen set off had settled down. Guitar slingers were hard to find, as were rock & roll bands. Billie Eilish, the preeminent new American pop star of 2019, admitted to talk show host Jimmy Kimmel that she'd never heard of Van Halen. A new generation will tend not to gravitate toward a band who essentially played oldies shows for the better part of twenty years, plus the band didn't necessarily build upon its brand during those two decades; the hits remained staples on classic rock radio and heard on TV, film and sporting events, an omnipresence that hummed along in the background. This fading isn't a tragedy so much as the natural order of things. Historical distance can be clarifying, though, and the further Van Halen's albums get from the center of culture, the more potent they seem as recordings. This sentiment doesn't apply exclusively to the Roth era — the first two albums with Hagar are well-oiled machines — but those six albums crackle with the excitement of a band who are intoxicated by discovering what they can do as a collective. It's the same energy that fuels Louis Armstrong's Hot Fives and Sevens, Hank Williams' MGM sides or Elvis Presley's Sun Sessions, the feeling of genius caught at the precise moment that it catches fire.