Enjoy Yourself: Terry Hall RIP

Farewell to the iconic lead singer of the Specials and Fun Boy Three

There was a moment in 1996 when Terry Hall rejoined the orbit of contemporary pop music, a good decade and a half after he left the Specials to form Fun Boy Three. It was a moment that arrived right in the thick of Britpop, a movement that would not have happened without Hall's music of the 1980s, a fact underscored by Blur inviting Hall to sing "Night Klub" on a 1996 television special. That year also brought Hall's appearance on Nearly God, the second album by Tricky, whose foreboding trip-hop owed as great a debt to the Specials as Damon Albarn's satiric celebration of British life (witness how The Great Escape contains a song called "Stereotypes," as did More Specials before it).

Tricky and Albarn were both eleven years old when "Gangsters," the debut single from The Specials, went into the UK Top Ten, so their affection for Hall isn't surprising: they seized a chance to sing with a childhood idol. The striking thing about Hall's resurgence in the mid-1990s is how it felt as if the world finally completed enough loops around the sun to return to where he always was, standing quiet and stylish, a wry scenester who can't quite bring himself to join the party so he will wait patiently until it comes to him.

Hall cultivated that persona in the Specials, a band where he provided a center of gravity among the joyful chaos. The lead singer but not the leader, Terry Hall didn't write the songs and allowed Neville Staple to overshadow him with his enthusiastic energy. His stillness wasn't recessive. Hall demanded attention with his affectless, accented vocals and his beautiful, mournful eyes, his careful composure standing in contrast to the riotous clammer of the Specials.

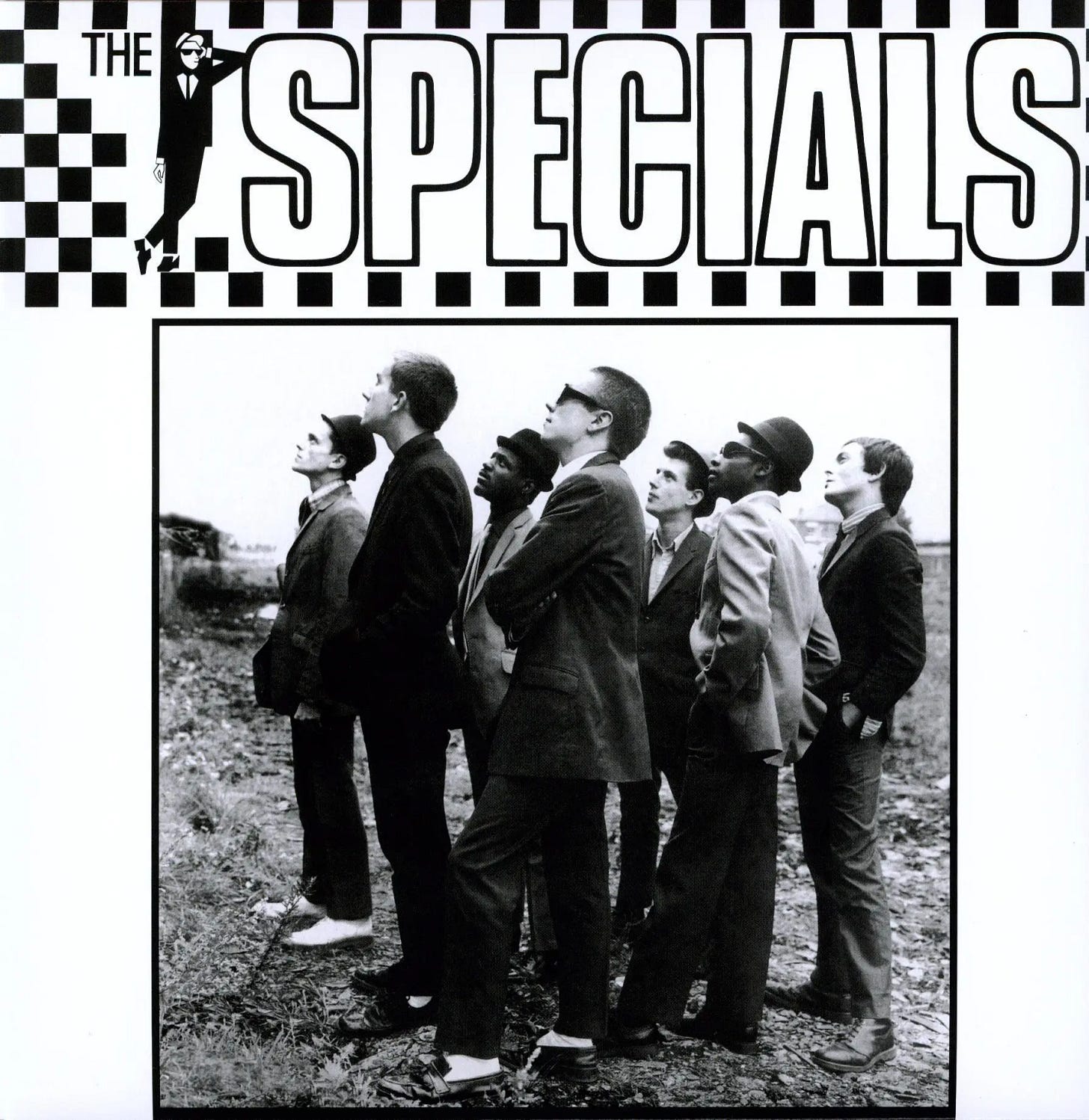

The Specials captured the cultural crosscurrents of the twilight of the 1970s better than any other band. Plenty of other punk bands played reggae but the ska revival the Specials spearheaded fused Jamaica and England in fiery, authentic ways: unlike so many of their peers, the group was mixed—they dubbed the blend "2 Tone," the name of their label and the subsequent musical movement they inspired—and the songs of keyboardist Jerry Dammers captured Britain in a state of societal turmoil. Their Elvis Costello-produced 1979 eponymous debut is a wonder, capturing their exuberance by underscoring how they weren't strict revivalists: they hit the beat like punk rockers, swung with soul, and cherished pop hooks.

That album was the sound of a collective but personalities soon emerged within the band, with Hall's spectral otherness turning him into a pop star while Dammers wanted the band to encompass social change and worldly musical exploration. It was too many ideas for one group so Hall and Staple brought guitarist Lynval Golding along to form Fun Boy Three, a group that used "Ghost Town"—an exquisitely unsettling portrait of a Britain in decline—as a launching pad for a group that crystallized so many of the eccentricities of their era. Take "The Lunatics (Have Taken over the Asylum)," a throbbing, ominous march with clear allusions to Reagan and other right-wing reactionaries: it's simultaneously haunting and silly, contradictory qualities that wind up as enhancements. Fun Boy Three revived musty pre-war pop tunes with a multicultural flair and sang Motown with Bananarama, while generating enough art and funk to gain the attention of David Byrne. A listen to "Our Lips Are Sealed," the radiant love song Hall wrote with Go-Go Jane Wieldlin during their brief affair, is instructive: the Go-Go's capture the giddiness of new love, while Fun Boy Three's version warily watches for the romance's inevitable end.

Hall could gravitate toward the dour but he also embraced the heightened tableau of pop music: he flitted through fashions, didn't avoid novelties, couldn't resist singing beloved oldies yet he was restless enough to compulsively cycle through projects throughout a decade that began with the 1984 debut of the Colourfield and ended when he and David Stewart decided to let Vegas be after one eponymous album in 1992. Hall made a lot of worthy music during this era: the bookends of the gorgeous reconstituted bossa nova of the Colourfield's "Thinking of You" and Vegas—where Stewart attempts to position Hall somewhere between Annie Lennox and Simply Red—are alluring artifacts of their time. There is a connective thread between Fun Boy Three and Vegas, particularly in how Hall's keening, plaintive voice is malleable enough to sustain seasonal makeovers while also being strong enough to be a recognizable constant, but the number of different projects effectively functioned as brand dilution: only the hardcore could follow all his whims.

Hall settled into a mellow, mature groove with Home, an overdue solo debut that emphasized rigorous pop values in its production and construction—values that rhymed with those championed by the legions of Britpop bands that were emerging in 1994, just as Home hit the racks. Working with chief Lighting Seed Ian Broudie, Hall leaned into the kind of tuneful, witty pop that was adjacent to his playful new wave: Andy Partridge, Craig Gannon, and Nick Heyward all were natural collaborators, helping accentuate his melodic instincts without dampening his quirks. Unlike Paul Weller's Wild Wood, Home didn't ride the zeitgeist: it's music for people stepping outside of the rat race. When his acolytes began dominating the British pop charts in the mid-1990s, he didn't take advantage of the opportunity so much as he co-existed with his disciples, accepting their invites while continuing down the subdued path carved out by Home.

The first decade of the 21st Century saw Hall collaborate with Mushtaq on The Hour of Two Lights and appear on records by Albarn's Gorillaz and reggae legends Toots and the Maytals, but Hall spent much of the 2000s dealing with personal issues. By the end of the decade, he returned to the Specials, reconvening a lineup without Jerry Dammers. A reunion tour in 2009 launched another decade of performances, as the lineup winnowed to just him, Lynval Golding, and Horace Panter. Augmented by such auxiliary musicians as Ocean Colour Scene's Steve Craddock, this reconstituted Specials released a pair of records that slide neatly into the band's oeuvre. Encore and Protest Songs 1924-2012 emphasize empathy, communion, and social justice, beliefs that were integral to every iteration of the Specials that nevertheless seem more valuable in the roiling 2020s. The albums also now play as a fitting farewell from Terry Hall, a homecoming to the sound and style that shifted the course of pop music in the 1980s.