It's Now Or Never: Catching up with Baz Luhrmann's Elvis and Roger Miller among other things

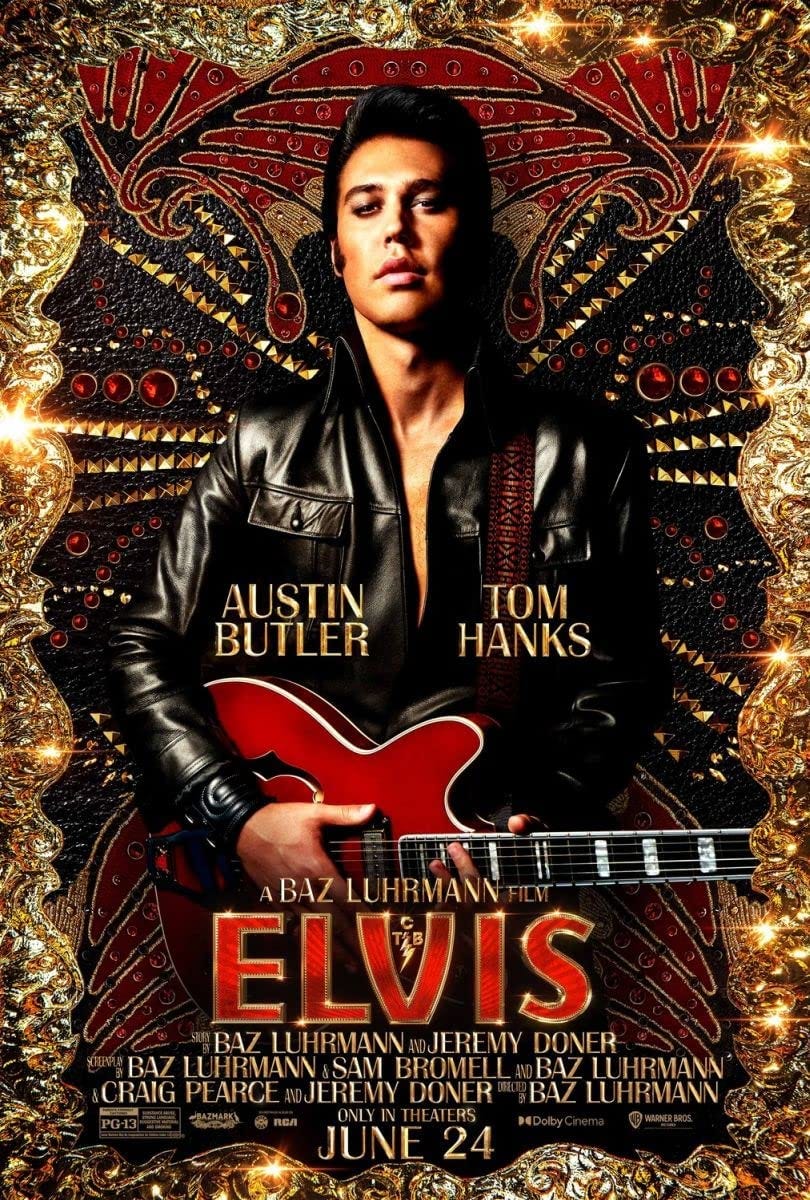

Sometime in the past month, a clip from Baz Luhrmann's Elvis Presley biopic started circling online, one where Col. Tom Parker is introduced to Presley's music through Jimmie Rodgers Snow, the son of country megastar Hank Snow. Parker and Hank are gobsmacked to learn Presley is white, a revelation delivered with the subtlety of a sledgehammer. Whether seen on its own or in the context of the film, it's a ridiculous scene yet it serves a crucial purpose, conveying how Elvis crossed and blurred the lines separating Black and white music—and culture—in the 1950s.

In traditional Presley lore, this task lands on the shoulders of Sam Phillips, the Sun Records founder who famously said "If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars," a quotation repeated so often it's been untethered from its original meaning. Often, these words are interpreted as a sign of racism rather than an acknowledgment of the racial politics of the 1950s, a culture where Black and white audiences were segregated in all aspects of life. Some crossovers did occur in the days before rock & roll, but Presley helped facilitate the breaking of barriers separating the races, not simply by bringing blues songs to white audiences but through his electrifying performances which touched upon blues and hillbilly, undergirded by pop showmanship.

Elvis isn't much interested in Presley's roots outside of the blues. Luhrman depicts the young Presley witnessing testifying at church or sneaking glances at juke joints, incidents that aren't technically accurate but feel true. The film takes great pains to portray Presley as part of the blues and R&B scene on Beale Street in Memphis, never once suggesting that he also listened to wild country boogie and treacly pop. The absence of the latter is especially odd considering how Luhrmann's heart truly resides in the melodramatic showman of Presley's last act when he built his act in Vegas and then toured it into the ground. Essentially, the film is divided into two: the first part chronicles Presley's rise to stardom, the second his fall, with the 1968 comeback special acting as the bridge between the two eras.

Dramatically, this feels so tidy that it takes a bit to realize how Elvis bypasses the bulk of the 1960s, the decade when Presley was at the height of his mainstream celebrity as a recording artist and movie star. Cutting these years from the story means there is no room for Presley's lighter, flirtier qualities, the elements that made him a pop idol: "Stuck on You" made him seem an ideal fantasy boyfriend. Flirty Elvis is one of the many Presley's missing in Elvis and that's fine: there's only so much room a feature film can cover. Even if the film wasn't framed as the story of Col. Tom Parker, the Presley of the 1960s wouldn't make the cut as that era isn’t as dynamic as the opening and closing acts, nor is it central to the working thesis from Luhrmann (and presumably Elvis Presley Enterprises): that Presley was not a craven appropriator but rather a creative artist seeking to control his own destiny.

Among Presley fans and scholars, this is hardly a new take on Elvis but the last few decades have seen his status calcify into a singer who either swiped his best ideas or sleptwalk through his career. Elvis is an effective counterargument to this tired line of thinking but it's strange to watch Luhrmann treat his subject so gingerly, even lovingly. He may not show much affinity for rock & roll but he takes pains to illustrate the thundercrack of Presley's arrival, then he treats the decline tenderly, placing the music at the forefront. As a biographical primer, it's effective, yet there's part of me that wishes Elvis was lurid and tasteless as the absurd section portraying the 1968 comeback special as a subterfuge on the part of Presley and his producers. Hanks' genuinely bizarre performance reaches a crescendo as he harrumphs around the studio demanding that Elvis sing "Here Comes Santa Claus," a negotiation that would've (and did) happen entirely backstage but is played out here as onstage melodrama complete with fake festive holiday sets constructed as a ruse. These are shenanigans worthy of Double Trouble and, frankly, Elvis could've used a bit more tacky silliness but that was never on the agenda. This was designed to revive Presley's artistic reputation and maybe rope in a few new fans and, against all odds, it fulfills its mission, likely because it paints an idealized portrait of the singer: he's an artist driven by passion and hemmed in by fame. It's not a modernization of Presley's story as much as it is a restoration which may be why Elvis has outgrossed all of the other Luhrmann's movies domestically (a bet I would not have made back in June): Baz treats Presley tenderly, an attitude that can please diehards and neophytes even if it leaves other viewers desiring a bit more shade and grey.

Further reading: My LA Times article about the state of Elvis Presley in 2022, published just before the theatrical release of Elvis.

HOUSEKEEPING

This indeed is the first newsletter I've published in a while and the reason for the delay is simple: I hit a wall parenting toddlers and tweens during the pandemic. Finding spare time to write the newsletter was difficult, especially when daycares would close due to COVID-19 exposures or when the disease spread through the entire household. I'd plot ambitious returns and then find myself unable to bring a piece across the finish line. Once I'm back in the swing of things, I'll polish off this material for subscribers but my current plans are to keep these missives focused on my current obsessions and interests, whether they are new or old. My apologies for the silence in this forum, and my sincere gratitude to all who read or care.

IN ROTATION

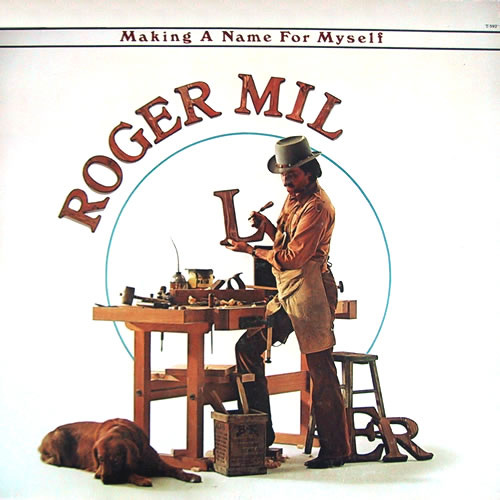

Roger Miller—Making a Name for Myself

Over the course of the summer, UMG has been unveiling a bunch of Roger Miller albums that never have seen the digital light of day. All of them are worthy but I'm hung up on this 1979 LP, maybe because it features "The Hat," which Miller performed on his episode of The Muppet Show but that showcase is a good indication of how thoroughly Making a Name for Myself is steeped in the culture of its time. It's country, sure, but it's slick, polished, funky, and friendly, the work of a showbiz natural who can't resist any variety show that came his way. Maybe he should've stopped himself before he committed "Disco Man"—a country-disco jape set to the tune of the nursery rhyme "This Old Man"—to vinyl but I'm glad he didn't, since he pulls off such cheap jokes with big, broad grin that's impossible to resist, even if the tomfoolery tends to overshadow the tenderness of such softer songs as "Old Friends"

Aaron Raitiere—Single Wide Dreamer

This one has likely been sitting on the shelf for a while as Miranda Lambert and Anderson East share production credits and it's been a long time since they've been partners of any sort. That provides a hook for the curious (or gossip mongers) but Single Wide Dreamer does kind of exist out of time, a soulful, laid-back record with deep roots and little affectation. Aaron Raitiere has a mellow drawl that's ideal for delivering punchlines and while those do come with some regularity here, the humor is too ingrained in the songs to be called jokey. He's a bemused spectator even of his own life and that relaxed, easy smile is plenty appealing.

Blondie—Against the Odds: 1974-1982

A capsule review and two quick takeaways from this mammoth box: 1) Unlike the (perhaps overly familiar) albums, the extra material conveys what an unusual, visionary band is, so it's worthwhile even when it's shaky demos and alternate mixes. 2) The Hunter is an unbearable slog.

WORK ELSEWHERE

Olivia Newton-John: An appreciation of the queen of 1970s soft-rock written for the Los Angeles Times. Nobody did mellow better.

Little Feat—Waiting for Columbus (Super Deluxe Edition): Went long on one of my favorite albums from one of my favorite bands.

Earl's Closet: The Lost Archive of Earl McGrath, 1970-1980: Rarities from stars and dashed dreams from obscurities in this snapshot of the private side of the golden age of album rock.

Ty Segall—"Hello, Hi": The garage rocker turns down the volume, revealing the Marc Bolan within.

Danny Elfman—Bigger. Messier.: This album-length remix of Big Mess sure is interesting, I'll give it that.