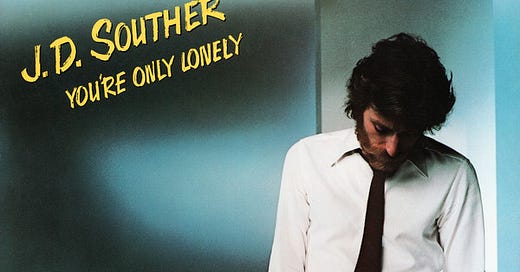

JD Souther RIP: If You're Only Lonely

An appreciation of the singer/songwriter who helped create the mellow Southern California aesthetic through his collaborations with the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, and James Taylor.

JD Souther never officially was part of the Eagles—he came close in the early days, deciding to pass on the gig after a test gig at the Troubadour suggested the band would be overstuffed with him aboard—but it's impossible to imagine the band's sunbleached soft-rock without the singer/songwriter. Working alongside Don Henley and Glenn Frey in various capacities, he co-wrote a long line of notable songs through the band's history: "Doolin-Dalton" "Best of My Love," "James Dean," "New Kid in Town," "Victim of Love," "Heartache Tonight" and "How Long," which wound up on their last album.

"How Long" is a song Souther wrote on his own, initially unveiling the tune on John David Souther, his debut album from 1972. By that point, he and Frey were old partners, veterans of Longbranch Pennywhistle, an amiable country-rock duo pitched halfway between Buffalo Springfield and the Flying Burrito Brothers. After releasing a likable, forgettable record in 1969, they went their separate ways. Souther swiftly discovered his gift as a conduit and collaborator, as well as an occasional muse. Judee Sill wrote "Jesus Was a Cross Maker" in the wake of her split from Souther and he'd have a relationship with Linda Ronstadt, producing part of her 1973 album Don't Cry Now, then writing and harmonizing on the blockbusters Heart Like A Wheel and Prisoner In Disguise.

Souther's work with Ronstadt coincided with the rise of the Eagles, a reflection of how all these musicians were enmeshed in a web that outsiders couldn't quite untangle. During this time, Souther's reach extended even further as he accepted David Geffen's invitation to form a supergroup alongside Byrds/Burrito veteran Chris Hillman and Richie Furay, late of Buffalo Springfield and Poco. Despite the pedigree, the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band never gelled as a band the way the Eagles did; they were three individual singer/songwriters, professional enough to turn out a pair of strong records, too ornery to follow somebody else's lead.

The implosion of the Souther-Hillman-Furay Band is odd considering how Souther proved himself to be a consummate collaborator in the rest of his career. Frey quipped that Souther didn't become a big star because he gave his best songs to the Eagles and Linda Ronstadt and to a certain extent that's true. Ronstadt brought a palpable yearning to "Faithless Love" and when Souther couldn't build a song around the gorgeous chorus of "New Kid in Town," he turned to Henley and Frey. His collaborative gift couldn't be charted through mere songwriting credits. Souther softened the cool reserve of the Eagles, suggesting the possibility of tenderness—a quality he also brought to "The Heart of the Matter," a rare moment of empathy from a solo Henley—his work with Ronstadt seemed like a shared secret, and he amplified the bittersweet ache in James Taylor's "Her Town Too."

Souther's ability to adapt himself to the needs of other musicians could mean that his solo albums sometimes seemed to lack a strong focal point. His sweet, slight drawl softened slightly when heard on its own, allowing the pros he surrounded himself with in the studio to take the spotlight. This reached an apex on Black Rose, his second solo album. Delivered in 1976 as SoCal soft rock crested to its peak, Black Rose featured everybody from Jim Kletner, Lowell George, and Waddy Watchtel to Stanley Clarke and Donald Byrd. The all-stars created a musical bed that was almost too supple, allowing Souther to ride the grooves instead of guide them, a trait that runs through the albums he made as a major label recording artist in the 1970s and 1980s. His light touch proved to be ideal for soft rock although it could tend to make his albums slightly too laid back. Even If You're Only Lonely, a companion to gilded The Long Run in every way—there's a fair share of frat-rockers refurbished to suit the scale of an arena—doesn't punch as hard as it could due to Souther's inherently warmth.

That warmth was certainly an attribute and not only on his exceedingly slick '70s albums. It helped Home By Dawn, the 1984 album that was his last record for nearly a quarter century, from drifting into glassy pseudo-New Wave territory. The warmth also matured gracefully. When he finally returned to recording in 2008 with the jazz-inflected If The World Was You, he sounded older but not weathered, the apparent age adding appealing texture to his crooning. The records he made during his last decades were handsome and tasteful, skillfully dodging the antiseptic pitfalls of modern soft-rock production. They, along with his recurring part on the Music City soap opera Nashville, created to a nice final act for his career, accentuating his charm as a performer in a way his core albums often did not. Those records were very much products of their time, capturing a certain sound and sensibility created by a collective of like-minded artists; Souther gets top billing but feels part of the team. On his latter-day albums, he's comfortable celebrating a reputation that only grew during his self-imposed absence from performing—Natural History indeed finds him revisiting his songbook—but he's relaxed into his idiosyncrasies, singing with an ease that he didn't quite manage during the mellow '70s. It amounted to an unexpected and graceful coda to an unconventional career, one that saw JD Souther become something of a cult figure even though he helped create the sound and aesthetic of mainstream rock.

I was really sad to hear about this, and glad he seems to be getting the recognition he deserves. Also - "a rare moment of empathy from a solo Henley" - lol