John Lennon's Mind Games Revisited

The casual 1973 album receives a six-disc "Ultimate" expansion

Mind Games exists at a crossroads, capturing the moment when John Lennon deliberately stepped away from the chaos of his own creation to stumble his way forward into the unknown.

Exhausted by the turmoil generated from his excursion into radical politics—a dalliance that brought him under the investigation of the US government while simultaneously shedding the mainstream audience he earned with Imagine—Lennon also reached his limit dealing with the fallout of the breakup of the Beatles. He, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr severed ties with Allen Klein—the manager whose hiring hastened the split of the Fab Four—early in 1973, not long after he approved the release of 1962-1966 and 1967-1970, a pair of compilations that wound up being unexpected chart hits.

The old Fab Four recordings were competing with new material from the solo Beatles, almost all of whom were doing well on the charts. On the back of All Things Must Pass and The Concert for Bangladesh, Harrison had another Top Ten hit with Living in the Material World and its single "Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)." Paul McCartney remained ensconced at the top of the charts while clawing his way back toward respectability with his new band Wings, while Ringo had a pair of number ones in his future with "Photograph" and "You're Sixteen."

Lennon, meanwhile, placed himself on the sidelines after Some Time In New York City, a politically-charged double album brought his career to a crashing halt in June of 1972. When the summer of 1973 rolled around, he realized too much time had passed: "I woke up and a year had gone by with no album." Once he heard the rough mixes of Yoko Ono's new recordings—he opted to sit out much of her Feeling the Space albums—he decided to head into New York City's Record Plant with her backing band of drummer Jim Keltner, guitarist David Spinozza, bassist Gordon Edwards and pianist Ken Ascher, all with the intention of knocking out an album quickly: he just wanted to get back in the game.

Prior to heading into the Record Plant, Lennon had a few songs completed—"Mind Games," "Only People," "Aisumasen (I'm Sorry)," "Bring on the Lucie" and "I Know"—but, as always, urgency was of import, so he decided to rush through the rest as the sessions started. Upon Mind Games' release in fall 1973, many critics noted its haphazard nature. In a Rolling Stone review, Jon Landau said the album had "his worst writing yet" and Robert Christgau said that after Some Time in New York City, it was "a step in the right direction, but only a step." Opinion softened on the album over the years—upon a 2002 reissue Anthony DeCurtis gave the album four stars in Rolling Stone — but not to the point that a limited Super Deluxe edition retailing at $1,350.00 seems necessary.

The Super Deluxe essentially is an art object anchored by Mind Games (The Ultimate Collection), a box set containing six CDs and two BluRays, along with a hardcover book. Even that box could seem excessive for an album that, by the estimation of Jim Keltner in an interview contained in this box's liner notes, was cut in five days in the studio. This problem is compounded by the fact Lennon finished many of the songs in the studio, so the "Evolution Documentary" disc tracing the creation of each song often sounds like Lennon jamming with a bunch of top-flight session men. Much of the box set plays in a similar fashion. The "Elemental Mixes" strip the recordings into a pseudo-demo, while "The Raw Studio Mixes" function as a retort to criticism that the proper album is too polished; there are no overdubs here—the lack of the signature soaring mellotron and slide guitar on the title track brings the song back to earth—just the core band following the lead of Lennon. (The "Elements Mixes" contain little more than highlighted instrumental sections; it feels like music for meditation.)

Lennon surrounded himself with familiar faces on Plastic Ono Band and Imagine, then slummed it with the dirtbag hippies of Elephant's Memory on Some Time in New York City, so these studio pros are a distinct change in direction for the ex-Beatle. They're slick, sure, but they have funk. Their easy interplay can be reason enough to listen: they provide a supple sway to the sweeter songs and give a bite to such bawdy throwaway rockers as "Tight A$" and "Meat City."

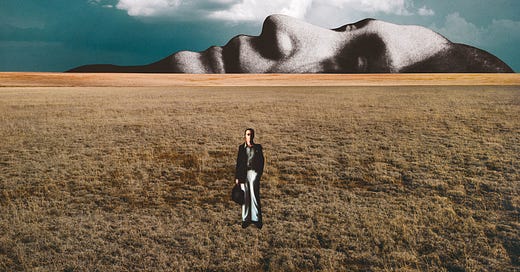

Neither "Tight A$" or "Meat City" could be called major Lennon tunes but they're crucial to the appeal of Mind Games. Lacking a grand vision for the album, Lennon attempts to muddle through the murk through "the magic of the music," as he sings in "Intuition." Try as he may, he's not quite creating magic on Mind Games. He doesn't have the material and he's too focused on moving forward, a desire conveyed on the album's cover which depicts John walking away from a mountain of Yoko looming in the background. Soon, he'd separate from Ono and head to Los Angeles, entering a period that's often classified as his "Lost Weekend" that nevertheless found him reconnecting with old friends and colleagues, once again seeming excited by the prospect of being a pop star. The germs of that breakthrough are contained here. It's clear that the musicians—unofficially called "the Plastic U.F.Ono Band"—enjoy following Lennon's lead as much as he enjoys playing music with them, a chemistry that gives the album an understated appeal even when its production veers toward the overblown. All the alternate mixes on Mind Games (The Ultimate Collection) attempt to scuff up that gloss but, ultimately, the charm of Mind Games is that it's a product of its time: it's a superstar stretching his legs with musicians whose talent matches his fame. It's not weighty which Lennon himself recognized when he said "it's just rock n' roll at different speeds." Sometimes that's all you need.