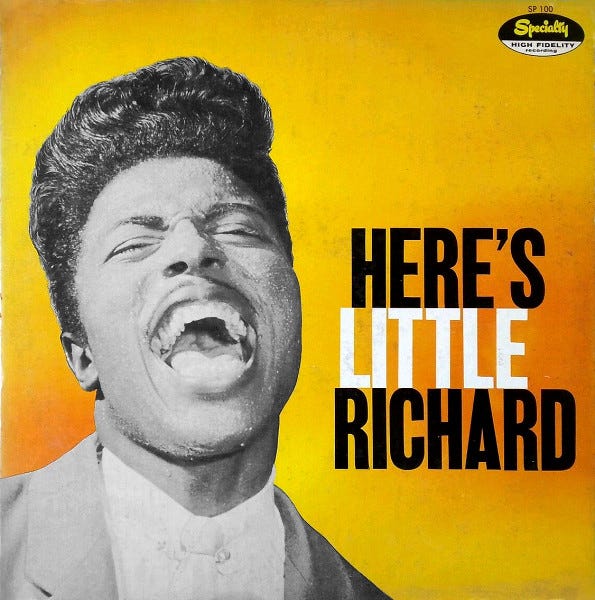

RIP Little Richard

Little Richard died this past weekend but his legacy hardened years and years ago. Alone among the surviving original rock & rollers, Little Richard maintained something kind of cultural relevance in the 21st Century, his outrageous persona being known and celebrated even if echoes of his music could no longer be heard on the pop charts. Richard pushed music toward the backburner decades ago but nobody noticed because his stardom eclipsed his origins: he was a loud, vivid presence, the walking definition of rock & roll.

All of his firepower was evident way back in 1957, the year he finally cracked the Billboard Top Ten after hovering on its fringe, his chart placement not reflecting his titanic influence on the nation's music and psyche. “Tutti Frutti,” his 1955 debut for Specialty, didn’t get any further than 17 on Billboard’s Top 40 but it is a seismic event in popular culture, a touchstone for how rock & roll wound up sounding the way it does. The list of classic rockers inspired by Little Richard seems so endless it's dull and reciting the names of his acolytes is weirdly counterproductive. Reducing Little Richard to an "early influence" dilutes his impact and importance.

"Tutti Frutti" wasn't the first rock & roll single ever recorded nor was it the first to climb up the charts—Chuck Berry got there first—but it was the first to feel as if it was sung by what we now know to be a rock & roll star: wild, furious and lascivious. Nobody else sounded like this back in 1955, not even Little Richard. He'd been grinding away for a while, working at the intersection of jump blues and New Orleans R&B, but his singles for RCA and Peacock were polite, even reserved. The same could be said about his earliest sessions for Specialty, a situation that frustrated the label's chief Bumps Blackwell. A September 1955 session at Cosimo Matassa's J&M Studios in New Orleans seemed destined to be another producing nothing of note, so Blackwell called for a break and took Richard to a bar where the pianist blew off steam by pounding out "Tutti Frutti," a bawdy celebration of anal sex he played during downtime at seedy joints. Blackwell realized he had to capture that version of Richard Penniman on record. He hired songwriter Dorothy LaBostrie to clean up the lyric but even if Little Richard was no longer explicitly singing about "good booty," his vocal was feral and carnal, so the single sounded dirty and dangerous. It sounded like rock & roll.

Lightning struck once for Little Richard and then it continued to strike over and over again for the better part of two years. That's how long he was at Specialty Records, cutting song after song that started in a frenzy and escalated from there. Variety wasn't Little Richard's strong suit. Of the sixteen charting hits he had in the 1950s only one was a ballad: "Send Me Some Lovin'," the flip side of "Lucille," one of his craziest numbers. Variety is overrated, though. Little Richard found a formula that worked, a sound and image that excited audiences, drawing upon his raising in the church and time on the chiltlin circuit—a period that included him dabbling in performing in drag—to create a persona that seemed otherworldly. He was a Technicolor hurricane in an era painted in drab black & white.

As much as anything, Little Richard's Specialty singles were vehicles for his own whirlwind of personality. With his relentless piano pounding, he seemed to be pushing the tempo, not the drummer—the mighty Earl Palmer adapted his style to keep things on track—and he shouted the words as if the meanings of the words were incidental. Which was true, in a way. Ever since LaBostrie sweetened "Tutti Frutti," Little Richard specialized in nonsense, spitting out gibberish or singing so fast all the words blended together. Maybe the words didn't scan but Little Richard's intent was clear: he found transcendence in earthly pleasures, a deliverance that could be heard and felt through his joyous shriek.

Each of his big Specialty hits deliver this rapturous jolt. "Long Tall Sally" teems with the delight of getting away with a sordid secret, "Ready Teddy" and "Rip It Up" are both gleeful with the anticipation of good times, "Jenny Jenny" and "Lucille" chase themselves in circles, "Good Golly, Miss Molly" and "The Girl Can't Help It" leer approvingly at women who own their own sexuality and "Keep A Knockin'" is two minutes of pure madness. Decades of repetition, covers, and appropriations haven't diluted the raw power of these sides, because they're all about Little Richard. Plenty of musicians sang his songs well and figured out how to elaborate on the bits they stole, but Little Richard's original performances are so exciting, they're almost exhausting.

Little Richard was built for speed and, appropriately enough, he burned himself out quickly. Plagued by the notion that he was singing the devil's music, he gave up rock & roll just two years after he cut "Tutti Frutti," turning to God and establishing his own ministry. He also attempted to straighten out his queerness, marrying Ernestine Harvin, adopting a son and putting on the airs of a normal life. All this fell apart around 1962, when he was lured by promoter Don Arden to play a headlining tour of Britain, a jaunt where he was treated like a conquering hero. Richard managed to turn this return into a modest comeback, signing with Vee Jay and landing an R&B hit in 1965 with the slow-burning "I Don't Know What You've Got But It's Got Me." At four minutes, it was twice as long as most of his Specialty hits but that was his only concession to changing times; it was a blues he could've sung at his old home.

Over the next two decades, Little Richard proved himself resistant to change. He'd dabble in a new sound, such as the high-charging post-Motown soul he played on 1967's The Explosive Little Richard, but he'd always return to the rock & roll that made his name. His last big shot at relevance happened in the early 1970s when he signed to Reprise during the heyday of the '50s rock & roll revival. Richard was game to try some funkier, fuzzier sounds and stretch out the title track of 1970's The Rill Thing out to ten minutes, but the fit didn't feel as natural as Chuck Berry playing naughty nursery rhymes for college crowds. After that spell at Reprise, Richard fell into years of abuse and neglect punctuated by religious revivals, finally staging a big comeback in the 1980s with the 1984 publication of Charles White's The Life And Times Of Little Richard: The Authorized Biography. A couple years later, he sang "Great Gosh A'Mighty! (It's A Matter Of Time" for the soundtrack to Paul Mazursky's Down And Out In Beverly Hills, a comedy that also featured him in a starring role. From that point forward, Little Richard figured out how to turn his outrageous persona into something so cozy and comforting, the only logical next move for him was recording a children's album for Disney in 1992.

He may have been omnipresent on talk shows, sitcoms, commercials, and even MTV, where he cameoed in clips by both Living Colour and Cinderella, but sometimes the old fire was still discernable. It could happen in concert but it happened most memorably at the 1988 Grammys, when he hijacked the presentation of Best New Artist to complain that "Y'all ain't never gave me no Grammy and I been singing for years. I am the architect of rock & roll and they never gave me nothing. And I am the originator!" He couldn't call himself the King Of Rock & Roll since Elvis Presley had been dubbed that years ago but Elvis himself covered a ton of Little Richard songs during 1956, the year both artists were at their creative peak. In a way, that says it all. Maybe he didn't outright invent rock & roll, but every rocker who followed him attempted to emulate in some fashion and listening to those immortal Speciality sessions, it's not hard to hear why. No other rock & roll sounded so raw or alive back in the 1950s and now that Little Richard no longer prowls the earth, his spirit can still be felt in that explosive rock & roll.