Who's Next/Lifehouse: Time Is Passing

Digging into a massive Super Deluxe Edition of Pete Townshend's abandoned rock opera

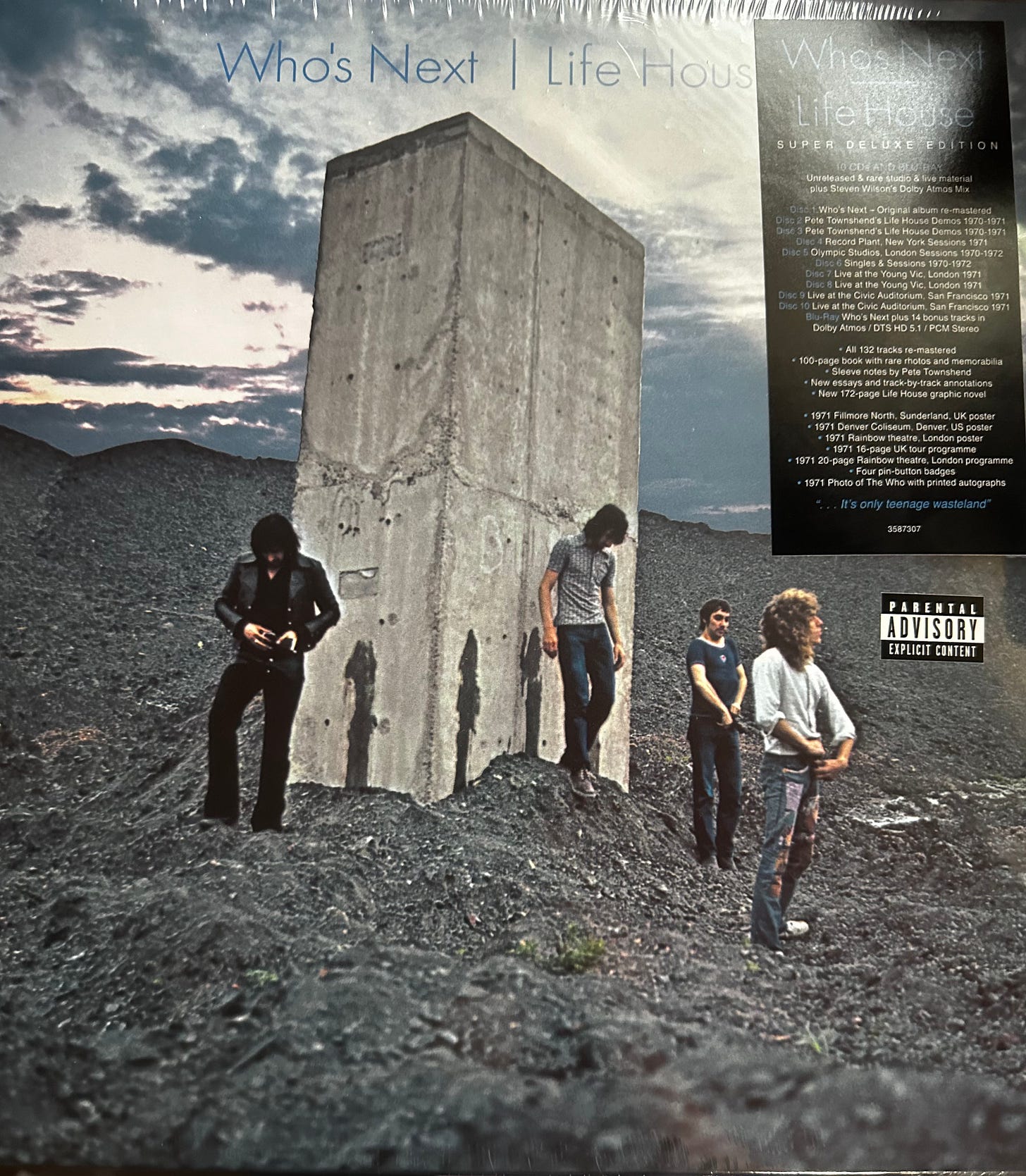

Who's Next can be a difficult album to hear. Curdled by overexposure on classic rock radio and mercenary licensing, its masterpieces are so thoroughly absorbed into the fabric of pop culture that they seem as immovable and dull as the monolith the Who huddle around on the album's cover.

It's a strange fate for an album that provided several distinct breakthroughs upon its release in 1971. Who's Next is where the Who finally harnessed their ferocity in the studio, an album that integrates electronic music with roaring guitars, a record that's at the cornerstone of the sound and culture of album rock, the sound that dominated mainstream rock from the 1970s through the 1990s, arguably even further.

Every beginning starts with a farewell and Who's Next marks a number of simultaneous endings, every one of which is tied to the band leaving the 1960s behind. During the album's convoluted conception, the band— specifically lead songwriter and conceptualist Pete Townshend—had a fatal fallout with Kit Lambert, the manager who helped shape and steer the Who's pop art bent in the 1960s. Pop doesn't play a big role in Who's Next, a considerable shift for a band that once specialized in singles as speedy and lacerating as news bulletins. Even Tommy, the album that catapulted the Who into the upper ranks of rockers, has its genesis in a quintessentially pop-art idea: What if rock & roll was also high art?

Many of the songs on Who's Next were intended for another rock opera, one far grander than Tommy. High on the ecstasy of Who concerts and lost in the teachings of Meher Baba, Pete Townshend envisioned a future without rock & roll, an era where the masses were fed virtual entertainment through an all-encompassing connective Grid. A dynamic, possibly prescient concept, Lifehouse inspired passionate, thoughtful songs but Townshend lacked a crucial element: he couldn't wrangle his ideas into a narrative, not even one as mushy as the one that drove Tommy.

On the verge of a nervous breakdown, Townshend agreed to take the best parts of Lifehouse and turn it into Who's Next, a record so precise and potent it never hints at its messy origins. Despite the massive, enduring success of Who's Next, Townshend never could leave Lifehouse behind. After a few songs slipped out elsewhere in the 1970s, he revived its central conceit for Psychoderelict in 1993, then he eagerly accepted an opportunity to turn the opera into a radio play for the BBC in 1999. That production brought Lifehouse Chronicles, a 2000 box set where Townshend unveiled many original demos, many of which are on the new Super Deluxe Edition of Who's Next, a weighty doorstep of a box featuring demos, outtakes, stray singles, and two full concerts from 1971.

This Super Deluxe Edition of Lifehouse is the first time the Who has released a Lifehouse project—maybe that's why it's inexplicably billed as "Life House" on the box's cover; I've standardized it to "Lifehouse" because that's how it's been known for decades—the realization of a dream that lingered for half a century. It's accompanied by a newly commissioned graphic novel that's perhaps the best rendering of Townshend's concept but it falls prey to the perennial Lifehouse problem: the intriguing philosophical questions are rendered stultifying when placed into the parameters of the plot.

Plot never was instrumental in understanding the emotional thrust the Who made during the sessions and concerts surrounding Who's Next, though. Emboldened by the success of Tommy, each member fell into larger than life pose, the trio of Roger Daltrey, John Entwistle and Keith Moon embracing all the spoils of success while Townshend clung to ideals that faded fast. Their volatile chemistry gained heft in the studio, particularly when produced by Glyn Johns. A late addition to the project, Johns stepped in as an associate producer when the album and the band itself threatened to disintegrate. He managed to make the Who sound like titans, his slight of hand erasing any trace of trepidation in the music. That sense of vigor is apparent not only on the outtakes and alternates from the Johns sessions but, oddly, to the Record Plant sessions that gave the band such pause early in 1971. On these outtakes, "Won't Get Fooled Again" may seem curiously thin, and "Love Ain't for Keeping" may seem a touch manic in its electric incarnation but the group sounds ferocious on a cover of "Baby Don't You Do It" and there's a tenderness to "The Note (aka Pure and Easy)" that got tempered in subsequent renditions.

"Pure and Easy" is a pivotal song on Lifehouse but on Who's Next, it's consigned to an allusion in the coda of "The Song is Over." Its absence on Who's Next is only felt if a listener is familiar with the album's backstory, history that's not needed for an appreciation of the original 1971 album but nevertheless illuminates the music the Who made during this period, hammering home how the Who were simultaneously on perched upon a peak and languishing in a valley at the dawn of the 1970s. The band's chemistry deepened as their execution sharpened, contradictions that were all too apparent to Pete Townshend, who wanted to harness the power of the band and their connection to their audience—an idea that fueled Lifehouse and drove him to the brink of madness. The extent of his plight is evident in how Lifehouse teems with hippie idealism, sentiments that previously were anathema to a rocker who kicked Yippie activist Abbie Hoffman off stage at Woodstock.

All the unheard songs from Lifehouse—nearly all of which have been in circulation for decades, thanks to the ceaseless march of Who comps and reissues—convey some form of communal faith and love, if not in fellow men then in nature or in the power of music. It's strikingly open-hearted music, particularly when compared with the flippant provocations and coded confessions of the Who's mod years, not to mention the weary cynicism that creeps in around Who By Numbers. There's a sense of hope and possibility flowing through this music, feelings that crystalize in the non-LP singles surrounding Who's Next, each feeling like a call to action: "The Seeker," "Let's See Action," "Join Together" and "Relay."

That all these singles are here, along with outtakes from early 1970, underscores how this Super Deluxe Edition conflates history somewhat by opening the prism to allow in everything the Who did as they struggled with moving forward from Tommy. It's very similar to how the Super Deluxe Edition of The Who Sell Out encompasses everything the band did between A Quick One and Tommy, a wildly prolific era filled with false starts, pranks, and masterpieces. This Lifehouse set applies a similar aesthetic to a considerably less flippant era, capturing all the might and mess of a band led by a songwriter whose yearning for transcendence was habitually hamstrung by the earthiness of his bandmates.

That tension can be heard in the bonus material on Lifehouse. Many of the Who's greatest songs and performances are spread over the three discs of outtakes and stray tracks: the aching "Pure and Easy," the mini-epic of "Water," the keenly drawn domestic drama of "Naked Eye," the mock country-rock of "Time is Passing" and "I Don't Even Know Myself." They're not sequenced as an album here—often, they pile up in remixes, sometimes with alternate vocals—so it can take some digging to find these individual gems yet immersion is also the pleasure of this set: the band never sounded better than they did in 1970 and 1971, so it's a joy to simply hear them play.

The mammoth size of the box also heightens the appreciation for Glyn Johns' masterful editing of this sprawl. Johns deployed Townshend's grandest songs as anchors on each side of the album, filling the remaining space that showcased the Who's brawn and spryness in equal measure. Maybe Entwistle's "My Wife" isn't a patch on "Pure and Easy" but it provides a necessary dose of thunder on the first side of the record, just as “Goin’ Mobile” offers a jolt of jubilation as Townshend finally shakes off the confines of his own mind and rides into the sunset. These moments are as key to the power of Who's Next as the bookends of "Baba O'Riley" and "Won't Get Fooled Again," twin towers that help a listener take measure of the distance traveled within 43 minutes.

The breathless efficiency of Who's Next serves as a testament to the benefits of a constricted commercial format: winnowing down this material to the confines of a single LP made the Who seem like an elemental force. Opening up the record with nearly nine hours of additional materials complicates that narrative considerably, restoring the contradictions and equivocations of Townshend, along with the crackling tension that could make the Who seem equally exciting and exhausting. The bonus discs also add some necessary historical context which mitigates some of the enervating aspects of Who's Next's overexposure: it doesn't freshen the album so much as return it to its moment of conception, a moment when the Who could still credibly speak to teenage dreams and had faith in something bigger. Knowing how the story played out can indeed make Who's Next seem like a tarnished masterpiece, particularly when it's reduced to a clutch of classic rock staples, but when it's presented in a fashion as gloriously messy as this, the music seems majestic, playing so free like a breath rippling by.